Environment

Snowy winter speeds drought recovery but Utah’s not in the clear

The unusable boat ramp at Great Salt Lake State Park in January 2023. Photo: TownLift // Kevin Cody.

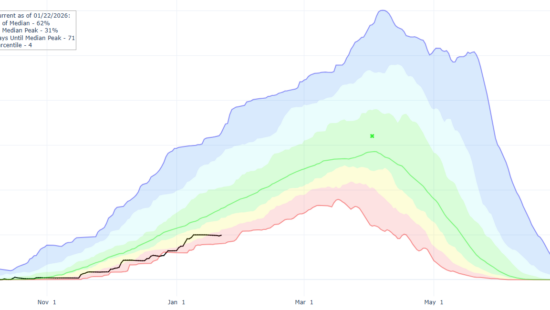

UTAH — Without even crossing into March, Utah’s snowpack is currently above the April peak at 196% above normal. While we could all live without the winter driving annoyances, all the snow will pay big dividends for the rest of the year.

For the first time in years, reservoirs will begin to fill, with some potentially reaching normal levels. Rivers and streams will be higher, improving Blue Ribbon fisheries like the Provo River. There are many tangible positives from having one of the best snowfall seasons of the last 20 years, but a complete recovery from drought is still going to take many years.

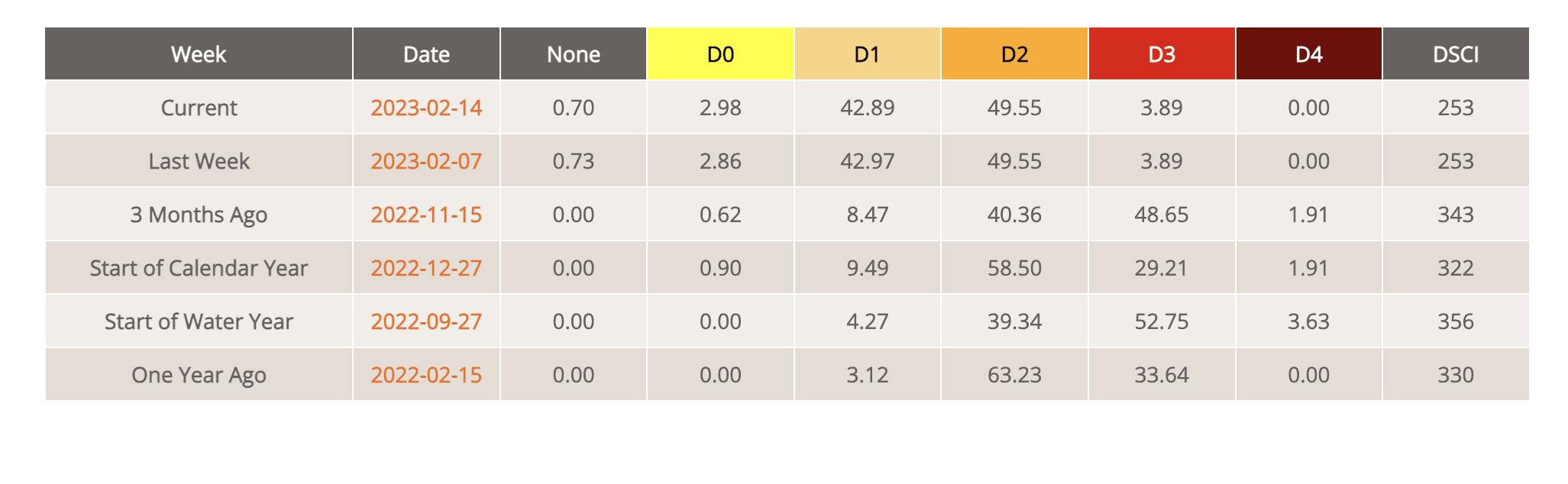

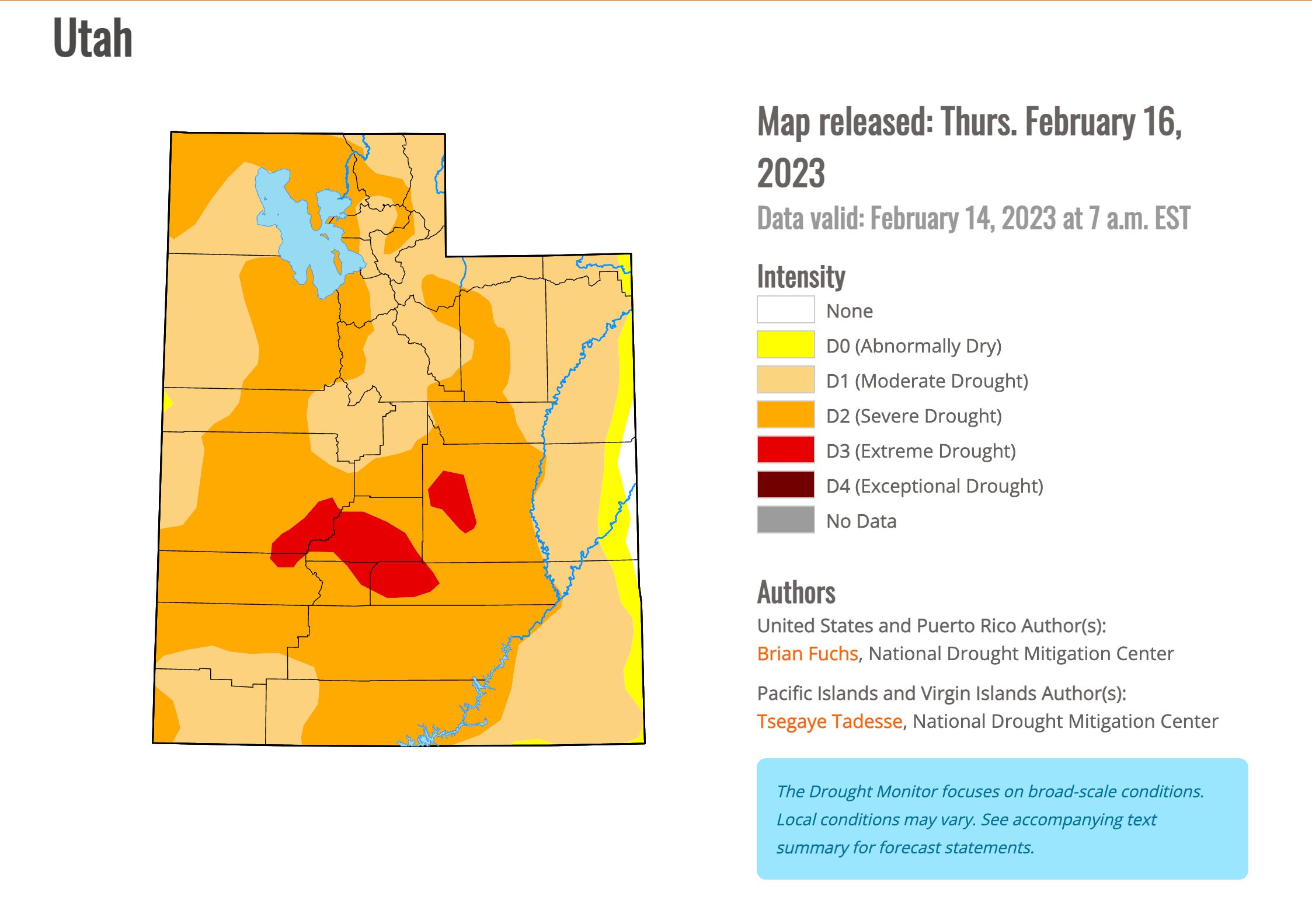

As of February 16, 49% of the state is classified as severe drought, 43% as moderate drought, and under 4% as extreme drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. While the severe drought percentage has gone up since November 2022, it only did so as a result of nearly 80% of the extreme drought areas improving to severe drought.

The same goes for the moderate drought rating, which went from 8% to 43%. All of Utah is still on some spectrum of the drought rating, but significant progress has been made since the fall.

“This is our opportunity year,” Candice Hasenyager, director of the Division of Water Resources, said. “In order to take full advantage of our plentiful snowpack, we must continue to use our water wisely. One good snow year won’t pull the state out of drought. And by using less water, we will become more drought resilient.”

Of the 47 reservoirs that the Utah Division of Water Resources (DWR) monitors, 24 of them are 55% below normal, with 10% of those lower than at this point in 2022. Yuba Reservoir is at only 19% of capacity and even worse is Gunnison Reservoir at only 3%.

In Wasatch County, Jordanelle and Deer Creek Reservoirs are at around 59% of capacity. DWR monitors 63 stream flows across the state, 24 of which are below normal levels.

More good news, the Great Salt Lake has risen by a foot. Also significant is Governor Cox’s executive order to raise the causeway berm by five feet or from 4,187 feet to 4,192 feet of elevation. The causeway separates the salty north arm of the lake from the south arm, where life is still holding on. The westernmost part of the causeway has an opening where the two halves mixed, but with the raised berm, that is no longer the case.

The lake’s silinity leve is key to the lake supporting life and effect on brine flies and brine shrimp. Levels are already affecting their reproduction and many areas where brine flies would lay eggs are now exposed.

If those two food sources were to leave, while there would be pockets where freshwater springs entering the lake would sustain some, there would be a devastating effect on bird populations.

Raising the berm has two main goals. The first is stopping the saline-saturated north arm from contributing to the problem of rising salinity. The second is to benefit from as much spring runoff as possible with the melting snow. While these two positives will carry some benefits, they will not stop the root of the problem, which is the reduced flow into the lake from human water usage.

To provide the public with up-to-date information on the Great Salt Lake, the Utah Departments of Environmental Quality and Natural Resources created a dedicated website where aspects such as current conditions, initiatives to save the lake, and other information. For tips on how to use less water, visit the Slow the Flow website.

The Great Salt Lake has risen by a foot but how does that affect its dire state?