Top Stories

Big Willow avalanche in May: survivor’s account provides important insights

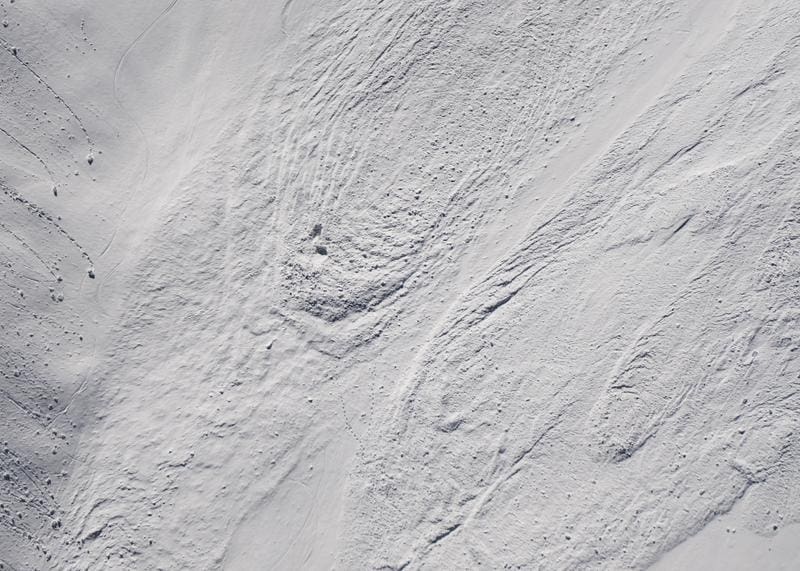

View from the top of the fin just below the ridge after the Lone Peak/Big Willow avalanche occurred. Photo: Utah Avalanche Center

The recently published Utah Avalanche Center report outlines the May 9, Big Willow avalanche on Lone Peak in detail, including the heroic but unsuccessful efforts of the survivor. Officials hope others can learn from the tragic accident that killed two.

PARK CITY, Utah – The Utah Avalanche Center has released its detailed report of the fatal avalanche that killed two men in Little Cottonwood Canyon’s backcountry area, known as the Big Willow Aprons, in May. In the report, many aspects of the accident are colored in, from a thorough report about the snowpack and conditions that day to exactly what unfolded when the avalanche released and swept all three skiers in the party down the mountainside.

The lone and unnamed survivor shared many details in the hopes that other backcountry enthusiasts could learn from the tragic event. Utah Avalanche Center’s Chad Brackelsberg said the report took a team of six, approximately 100 hours to prepare. He added that interviews with the survivor of the tragic event were key to putting together a complete picture of what happened.

“We recommend people read the full report, there’s so much good learning in there,” Brackelsberg said.

The avalanche occurred on May 9, after a late-season storm left several feet of new, cold snow in the heart of the Wasatch mountains. Austin Mallet, 32, of Montana, and Andrew Cameron, 22, of Utah, died in the avalanche, and rescue crews had to abandon recovery efforts to return the following day to bring their bodies off the mountain.

On the morning of May 9, the three skiers started their day hiking in running shoes from the side of SR 210 near the Y Couloir, which they had planned on skiing for the final run of their well-planned ski tour. After about 2 miles of hiking up the Sawmill trail, they switched to ski gear and began skinning through the Big Willow drainage. They intended to use the Big Willow Aprons as an approach to Lone Peak.

During the ascent, and roughly 150 feet from the top of the rocky ridge, the party transferred their skis to their backpacks and started bootpacking to gain the ridge, wallowing through the deep, fresh snow. The man who survived the slide was in the lead and had just crossed over a rocky terrain feature—called a fin—when the avalanche broke above him and swept him down one side of it. The report states that he tumbled and cartwheeled down the slope for 300 feet before he came to a stop, partially buried.

“He took off his glasses because he couldn’t see, coughed up snow, and dug himself out. At the time, he thought he was the only one caught and believed Austin and Andrew were waiting for him on the other side of the fin (looker’s left). He skied down to the bottom of the fin, turned around the base, and saw the other side (looker’s left) had avalanched even bigger,” the report said.

The man yelled out for his two friends, switched his avalanche transceiver to receive mode, and began searching for Mallet and Cameron. After locating a signal, he noticed a ski on the surface of the avalanche debris and moved toward it. About 13 minutes after the avalanche occurred, he was able to locate Mallet and partially uncover him. The survivor gave a few rescue breaths to his friend but could not get a response.

Minutes later, he located Cameron, uncovered his head, cleared his airway, and attempted to administer rescue breaths to no avail.

At 10:18 a.m., approximately 34 minutes after the avalanche occurred, the man called 911 and continued to unbury his partners while waiting for help to arrive.

“Subtle” factors to blame for slide

While some avalanches are easy to explain, experts say this one was much more nuanced—so much so that even the three very experienced skiers who were caught in it weren’t able to assess the risks.

“Given the area over which this avalanche fractured and the subtle wind effects observed at the scene and reported by the survivor, we are not sure of the exact character of this avalanche. Strong winds likely played some role in forming a slightly more cohesive slab on the leeward side of the rocky rib or fin, but it was not very obvious. We are unsure what the weak layer was in this avalanche,” the report said.

In addition, the last report issued by the Utah Avalanche Center was posted on May 1. It is common practice for the organization to stop posting daily reports around this date in the spring, in part because conditions can change drastically and very quickly in the spring, making daily forecasting especially difficult, if not irrelevant.

“In the spring time, here in Utah we are dealing with a different set of problems than in the middle of the winter and those problems are very localized,” Brackelsberg said.

In the morning there could be new snow and storm slabs and by the afternoon those problems turn into wet avalanches. The sun in spring is more direct and affects, the south-facing slopes especially, very rapidly. More information about spring problems in the backcountry can be found here.

Key Takeaways from the Big Willow Avalanche

Many more nitty-gritty details about the snowpack—complete with snow profile and weather charts—can be studied in the full report, but the UAC stressed five key takeaways.

- Exposing one person at a time in avalanche terrain is one of the fundamental “rules” of safe travel. However, many skiers ascend avalanche terrain at the same time when they believe conditions are stable, more commonly in the spring. At times, this may be appropriate given many factors, but it means a higher level of risk and requires a higher level of confidence in stability.

- Close proximity burials can be especially challenging in a transceiver search due to the signal overlap of the nearby transceivers. Multiple burials are challenging regardless and can significantly reduce the odds of survival.

- Electronic devices like GPS watches, phones, GoPros, etc., can interfere with transceiver use. It doesn’t appear that interference was a factor in this accident. The current solution is a 50 cm (20 in) separation between the device and the searching transceiver. Wearable devices like watches or heated gloves can be problematic because it is difficult to get separation. Holding a transceiver in the other hand or removing heated gloves are solutions, but these actions could be difficult to remember during a stressful situation.

- The survivor commented that he was frustrated with his smaller shovel size and would recommend a larger shovel, which can move significantly more snow faster.

- The three skiers were all strong, experienced mountain athletes. Despite their skill sets, sometimes accidents happen with tragic outcomes. Mountain travel is inherently dangerous and even the best of us can find ourselves in trouble.

Appreciate the coverage? Help keep Park City informed.

TownLift is powered by our community. If you value independent, local news that keeps Park City connected and in the know, consider supporting our newsroom.