News

Need for affordable housing runs up against Utah zoning laws

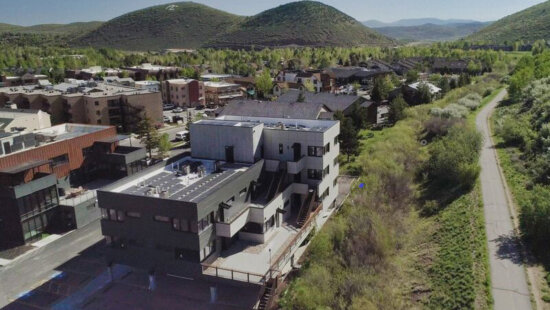

“We need to have a statewide conversation about growth. Because if we aren’t intentional about it we’ll probably end up with something we don’t like.” Photo: TownLift

SALT LAKE CITY — A growing chorus of experts say middle housing, a class of multifamily housing options that falls between single-family homes and large apartment complexes, is a vital instrument in the fight against unaffordable housing.

But middle housing has a big problem: Zoning in most residential areas doesn’t allow it, the Deseret News reported.

That’s the big takeaway from a new report from the Utah Foundation, which challenges the wisdom of the prevailing 20th-century zoning practices that separate commercial and residential areas while catering to automobile-oriented development, making the case that zoning laws, predominantly under the jurisdiction of local governments, is hampering affordability.

The report, Obstacles and Opportunities, released this month, is the fourth and final installment of the Utah Foundation’s “Missing Middle Housing” study, which offers a comprehensive overview of the character, viability and impacts of a category of housing stock the foundation says is needed to help bring the state’s stratospheric housing costs back down to earth.

As an example of regulatory obstacles, the study shows that in Salt Lake County more than 88% of residential land is zoned for single-family homes that fail to fulfill demand, which is representative of other areas along the Wasatch Front.

This means developers pursuing middle housing in existing communities must obtain conditional-use permits or rezone approvals, a process whose low success rates and added administrative expenses have increasingly deterred building projects that would diversify the state’s housing portfolio.

“After sitting through hundreds of public hearings, I’ll say it’s nearly impossible to get middle housing projects in single-family zones,” said Nate Pugsley, founder of Brighton Homes, which specializes in middle housing projects.

Pugsley explained that when developers seek city approval for general plan zoning amendments to allow middle housing in single-family areas, “that is like warfare. For most cities redoing spots of their general plan is opening a can of worms. People come unglued over it, and so cities won’t brave it.”

Of course, stalwart single-family standards are coming from commissioners and elected council members, whose reticence toward increased multifamily housing reflects the preferences of their constituencies, a point on stark display in surveys cited in the Obstacles and Opportunities report.

The surveys, conducted by Envision Utah, find that even as Utahns are increasingly worried about home prices, they maintain strong opposition to new housing projects in their vicinity.

One-third of respondents agree with the statement: “I am more comfortable with development in other nearby cities or towns, but not in my own community.” One-third were neutral and about the final third disagreed.

“You see results where 80% say they support a wide variety of housing options, but where that breaks down is when they say, ‘But not next to us.’ When that happens in every community, then you don’t actually get the housing scenario that people say they want,” said Ari Bruening, CEO of Envision Utah, who believes the aversion to neighborhood housing reflects an overarching concern with general growth.

“We’ve seen in the last seven years a rise in concern about growth. Utahns are really feeling high housing prices, increased congestion, and that’s starting to translate into opposition to new housing and people are saying, ‘I don’t know where this is heading, so let’s just slow down.’”

Bruening’s point is shown in another survey question that shows half of respondents believe “Utah communities should approve less housing in order to slow growth.”

If you do not build it, the responders seem to suggest, then they will not come.

Although, with the state’s historically declining but still competitive birthrate, along with an attractive tech industry that continues drawing job seekers, renters and prospective homeowners may show up anyway.

“I guess we could ruin our economy and our quality of life, and then we’d stop growing. But as long as we have a high quality of life and a prosperous economy we’re going to grow. You can’t stop that,” Bruening said. “So the real question we ought to be asking ourselves is not how do we slow or stop growth, but how do we accommodate it in a way that retains the quality of life that we’d love in Utah?”

Growth anxiety is currently on display in Tremonton, in Box Elder County, where city leaders recently annexed a 135-acre area into the city with the intention of implementing the River’s Edge development, a mixed-use overlay zone accommodating up to 750 new units of single and multifamily properties.

The project quickly met the ire of longtime residents who decry rapid expansion and spawned a signature gathering effort to repeal the development by way of the ballot — a campaign calling itself Slow the Grow.

“I think part of it is growing pains. We’re growing really quickly and growth is coming from within and outside of our city. On the one hand there’s an affordable housing crisis, but on the flip side, there are issues that are important to our current residents and the city doesn’t disregard what the residents’ concerns are,” said Shawn Warnike, Tremonton city manager.

Slow the Grow is concerned the River’s Edge development “will lead to a massive change in our historical culture and massive property tax increases resulting from the need for new schools, more culinary water, an enlarged or new wastewater treatment facility, additional full-time police officers, fire fighters, and EMS personnel, enhanced roads, and so much more,” according to a recent Slow the Grow op-ed.

Warnike responded by saying, “I felt the city negotiated a good deal. We put a lot of forethought into the layout to make sure we could provide services and better the community and surrounding neighborhoods by adding improvements. But this (ballot) process is clearly what is allowable in the state code and whatever the outcome is we will adjust from there.”

Those affiliated with Slow the Grow are among the high percentage of Utahns politically motivated by concerns over growth. The Utah Foundation’s report cites surveys indicating, “more than one-third of residents … would attend a city council meeting to oppose a proposed development — more than any other reason. Growth-concerned Utahns are more likely than others to have attended a city council meeting.”

Beyond reaching a consensus about appropriate density levels, middle housing advocates must also address another big issue: one of America’s most sacrosanct objects — the automobile — whose parking allotments are overindulgent, the report says, which creates land-use inefficiencies that drive up the costs.

But deprioritizing car-oriented development could be a long haul.

“If you try to minimize parking, you get some backlash from people saying, ‘Hey, wait a minute, we don’t want to be New York City. I want to have an empty parking space that’s always there waiting for me so I can park close and don’t have to spend time in my car looking for parking,’” said Shawn Teigen, vice president and research director at Utah Foundation. “But they need to know there are trade-offs.”

The foundation’s research offers a strong argument for reevaluating zoning standards around parking. The work explains how parking requirements in Utah cities are determined using data from the Institute of Transportation Engineers, which offer statistics about parking demand among other datasets. However, analyzing research from the Metropolitan Research Center at the University of Utah, the foundation report revealed that cities and counties rely on ITE estimates that focus mainly on suburban areas with limited transit and walkability, which becomes self-fulfilling of sprawl. Local governments also plan based on measurements for peak demand periods, resulting in development with parking spaces that stay vacant the majority of hours, according to cited the report.

“One of the things we say is that for every car in the United States, we’ve got eight parking spots. And is that really necessary? Especially if you take examples of high commuter are usage and blanket that requirement across the board, you’re going to end up with more parking than you need. It’s not applicable to all places and we need to relax a little bit,” Teigen said.

But for many Utahns facing onerous housing costs, the stronger argument to cut back parking lots is the promise to shave down rent. One study cited in the foundation report found that parking spaces add an additional $225 per month on average to apartment rents in Utah.

“If you’re requiring that every new unit has two parking spaces, that limits the number of units you can put in because you can only go so high. If you’ve got an eight-plex and you need 16 parking spaces then that takes up an inordinate amount of space. We’re going to need to change what our expectations are. And one of those is parking. Without addressing parking, we’re gonna have a really hard time ever reaching affordability,” said Teigen, who explained that increasing the ratio of units to parking also renders projects more profitable and will motivate developers to meet demand.

The silver lining for the foundation is that while opposition to new housing remains strong, evidence suggests residents warm to development when looking at Utah issues holistically; when advocates display the broader connections between new housing, affordability, sustainability and quality of life, attitudes toward gentle density soften, as Utahns appear to want younger generations to have options, too, and are slowly appreciating the consequences of perpetual sprawl.

“We know people want larger yards, larger homes, more parking spaces. But when you ask if they think it is important to have affordability in neighborhoods and affordability for younger Utahns, people say yes. When we ask if they want their kids and their grandkids to live near them in the future, they say yes,” Teigen explained, “So focusing on those things and explaining how this is all connected is part of the challenge. You’ve got to sell it.”

Bruening of Envision Utah says said conversations about Utah’s growth realities are urgent and believes all communities need to play a part.

“We need to understand in Utah we have geographic constraints to our growth. You can’t just add another ring of suburbs because you hit mountains and lakes, and so does the next ring in the next valley over. It adds to commute times, and in a lot of cases puts people in the middle of our best farmland. Communities need to accommodate more housing, and I think every community has it has a part to play,” Bruening said. “We need to have a statewide conversation about growth. Because if we aren’t intentional about it we’ll probably end up with something we don’t like.”

The foundation’s earlier work shows that communities may have an easier time playing their part if developers and zoning authorities meet in the middle on design principles, considering Utahns are more amenable to new housing when the aesthetics are agreeable and projects have the appearance of single-family housing.

Although for middle housing advocates, it’s about more than bringing prices down — rather, it’s part of a bigger initiative to create livable communities that are connected, sustainable, and perhaps above all, walkable.

“The idea with missing middle housing is that if you create a little more density and look beyond the old zoning and toward form-based code, you’ll get more of a mix of residents and businesses which gives you a higher percentage of trips that are walking or biking. These are communities with more of an active element to them. You won’t have to get in your car every time you need to make a trip,” said Teigen.