History

Reclaiming relationship: Shoshone teachings on shared stewardship in Summit County

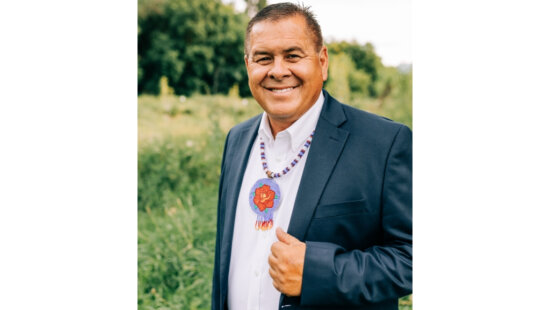

Darren Parry, former chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, shares Indigenous teachings about the land, water, and mountains of Summit County as part of an ongoing TownLift series exploring Native history and perspectives rooted in this region. Photo: Darren Parry

Darren Parry is the former chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation and a respected Native leader, historian, and educator. He serves on the board of directors for the American West Heritage Center, the Utah State Museum board, and the advisory board of the Huntsman Cancer Institute. Parry is the author of Tending the Sacred: How Indigenous Wisdom Will Save the World and The Bear River Massacre: A Shoshone History. He also teaches at the University of Utah and Utah State University.

Each November, as communities across the country reflect during Native American Heritage Month, TownLift reached out to Darren to better understand the longstanding relationship between the Shoshone people and the land now known as Park City and its surrounding mountains. In this conversation, he shares teachings that continue to live in the land itself, offering guidance for how we might show up with greater care, awareness, and connection.

RB: How would you describe “shared stewardship” from a Shoshone perspective, and how does it differ from the way we usually think about land management or conservation today?

DP: From a Shoshone perspective, shared stewardship is not a policy framework—it is a relationship. It begins with the understanding that the land is not a resource, but a relative. The mountains, the rivers, the animals, the plants, and the people are part of the same family, and because of that, we share responsibility for one another’s well-being. Stewardship is a living covenant between human beings and the natural world, formed over thousands of years of observation, reciprocity, and accountability.

In the Shoshone way of thinking, no one “manages” the land. The land manages us. The land teaches us what is needed, when it is needed, and what our role must be. Our job is to listen. That is a very different starting point from modern conservation, which often begins with science, regulations, budgets, and resource planning tools. Those are useful, but they are incomplete if they are not grounded in relationship, humility, and long memory.

For us, stewardship is shared across generations. You make decisions not only with today’s needs in mind, but with seven generations ahead of you in the circle. If you cannot defend your choices to the faces of children not yet born, then you are not practicing stewardship in the Shoshone sense.

Modern conservation approaches often frame stewardship around protection, preservation, or extraction:

- How many trees can we cut and still be sustainable?

- How many sage grouse are needed to keep the population viable?

- How can we balance development and recreation?

Those are understandable questions, but they are rooted in a worldview that sees land as something to be measured, controlled, and optimized. Our perspective asks different questions:

- What does the land need to remain alive and whole?

- What practices will strengthen the relationship between people and place?

- How do we include the voices that have been removed from the table—elders, ancestors, children, and the land itself?

Shared stewardship also means shared authority. Decisions about a landscape should be shaped with the Indigenous nations connected to it—not after the fact, not symbolically, and not as a courtesy. If the history of the land is shared, if the impact is shared, then the responsibility must be shared as well.

So, from a Shoshone perspective, shared stewardship is not merely a strategy—it is a way of living that honors the truth that the land isn’t something we own. It is someone we belong to. It is someone we are accountable to. And when we remember that, stewardship stops being a task and becomes a shared promise.

RB: For those of us who live in Summit County now, what does it mean to reclaim a relationship with the land, knowing it was once the Shoshone homeland?

DP: For those living in Summit County today, reclaiming a relationship with the land begins with acknowledging a simple but profound truth: you are living on someone’s homeland—on a landscape that carries stories, knowledge, and memory far older than any road, building, or county line. Before this place became “Summit County,” it was a living cultural landscape of the Shoshone people. Our villages, hunting grounds, medicines, ceremonial spaces, and seasonal camps were woven into the land like threads in a blanket.

But reclaiming that relationship does not mean trying to become Shoshone or looking backward with guilt. Instead, it means choosing to live in this place with the same kind of respect, attentiveness, and reciprocity that the land once taught us.

For new residents, several things matter: Healthy relationships begin with remembering. Reclaiming a relationship with the land means understanding who lived here, what they believed, and how they survived with the land—not from it. It means recognizing that Shoshone ways of living were not primitive; they were sophisticated systems of ecological intelligence honed over thousands of years.

When people learn that history, they begin to belong differently.

Many of us today see land in terms of what it can provide: a view, a ski run, a foundation to build on, or a natural resource to manage.

The Shoshone way asks different questions:

- What does this land need to stay alive?

- How do we live here in a way that leaves the place healthier than we found it?

- How do we become good relatives to soil, water, wildlife, and one another?

When you ask those questions, stewardship becomes something deeper than environmental policy—it becomes a way of being.

To reclaim a relationship with the land, you must learn to see it not as scenery but as kin. The ridges, the creeks, the sagebrush flats—they are teachers. They carry instruction, if we are willing to pay attention. For thousands of years, Shoshone families learned the rhythms of this place by watching animal migrations, plant cycles, snowpack, and the river’s changing mood. That kind of observation builds intimacy. Anyone can learn that—if they slow down long enough to listen.

Modern society often treats land as something we own. From a Shoshone perspective, land is something we are in partnership with. That partnership requires reciprocity: If the land gives, we give back. If the land hurts, we respond. If the land changes, we adjust with humility.

Reclaiming relationship means moving from entitlement to gratitude. Reclaiming relationship means recognizing that Indigenous people are still here, and still have knowledge to contribute. It means inviting collaboration, not for appearance or checkbox compliance, but because solutions born from the land must include those who have lived in deep conversation with it the longest.

When Summit County residents learn with us, not just about us, they begin to rebuild something that colonization tried to sever: a living, ongoing relationship between people and place.

It means choosing to live here as relatives, not renters. It means remembering that belonging is earned through care, not title deeds.

And it means recognizing that the story of this land did not begin with you, but can continue through you if you choose to steward it with the same reverence that has sustained the Shoshone people since time immemorial.

RB: Many of us were raised to see land as property. What helps shift that mindset toward reciprocity and belonging rather than ownership?

DP: For many of us, the shift from seeing land as property to seeing it as a relative begins with changing the stories we live inside. If we are raised to believe the land belongs to us, we will treat it as something to control, manage, or extract from. But when we begin to understand that we belong to the land, the relationship changes completely.

From a Shoshone perspective, three things help create that mindset shift:

- Paying Attention: Reciprocity begins with noticing. When people spend time on the land, watching the seasons, the migrations, the shifts in plants and water, they begin to understand the land is not an object, but a living system with its own needs. Relationship requires presence.

- Practicing Gratitude: Daily gratitude is one of the oldest Indigenous teachings. When you thank the river for its water, or the sage for its medicine, you remember that you are receiving a gift. And when something is a gift, you have a responsibility to care for it in return.

- Learning Its Story: Belonging comes from knowing who came before, what was harvested here, what ceremonies took place, and what the land has already survived. When people learn the land’s memory, they begin to feel accountable to it—not just connected to it.

So, the shift away from ownership does not happen through policy alone.

It happens when people begin to ask different questions:

- What has the land given me?

- What does it need in return?

- How do I become a good relative?

When those questions replace the idea of possession, stewardship becomes not a legal duty but a shared, ongoing relationship.

RB: What are some everyday ways people in Park City and Summit County can begin to live with more awareness and respect for the land — through learning, listening, or gratitude?

DP: People in Park City and Summit County can begin living with more awareness and respect for the land in simple, everyday ways—changes that build relationship over time. A few examples include:

- Spend time outside with intention: Walk, ski, or hike not just for exercise, but to notice what the land is showing you—weather shifts, plants returning in spring, wildlife patterns.

- Learn the history of the place: Know whose homeland this is, what stories the Shoshone carried here, and how people once lived with the land rather than above it.

- Practice daily gratitude: Thank the land for the water you drink, the food on your table, the snow that sustains your economy. Gratitude creates responsibility.

- Use your footprint wisely: Conserve water, reduce waste, support local stewardship efforts, and make choices that leave the land healthier than you found it.

- Listen to Indigenous voices: Attend talks, read Native authors, support tribal partnerships, and seek guidance from those who have been in relationship with this landscape the longest.

Small acts done consistently build a new way of belonging—one that honors the living world, not as property, but as a relative.

RB: How can local governments, schools, or organizations build more meaningful relationships with Indigenous communities in caring for these lands together?

DP: Local governments, schools, and organizations can build more meaningful relationships with Indigenous communities by moving from symbolic gestures to real partnership. A few practical steps include:

- Invite tribes into decision-making—not after plans are written, but from the beginning: Shared stewardship means shared authority, not ceremonial consultation.

- Build long-term relationships, not one-time projects: Trust grows when collaboration is ongoing, consistent, and grounded in mutual respect.

- Support Indigenous cultural and ecological knowledge in schools: Bring Native educators, elders, and curriculum into classrooms so students understand the real history—and living presence—of this land.

- Create agreements that transfer resources, not just expectations: Partnership means resourcing tribes to participate fully—because their knowledge benefits everyone

- Honor place-based storytelling and ceremony: When Indigenous communities are welcomed to practice culture on the land, the land itself becomes a partner in the restoration of relationship.

When institutions move from “teaching about Native people” to working with Native people, stewardship becomes richer, more grounded, and more capable of sustaining the land for generations to come.

RB: If you could ask every resident and visitor to reflect on one question before stepping onto these mountains, what would that question be — and why?

“How will my presence honor this place?”

I chose that question because it shifts the mindset from consumption to relationship. Instead of asking what the land can give, beauty, recreation, escape, we begin asking what we can give back: care, humility, awareness, and responsibility.

When people enter the mountains with that intention, they walk differently. They notice more. They take less. They remember they are guests in a homeland that has held stories, families, and lifeways far longer than any of us have been here.

If we ask that question every time we step onto the land, we begin to belong to the place in a way that sustains both the land and ourselves.

Editor’s Note: This interview is part of an ongoing series exploring Indigenous history, culture, and perspectives in Summit County.