History

Ancestral Shoshone teachings call for balance, as Park City faces pressure to grow

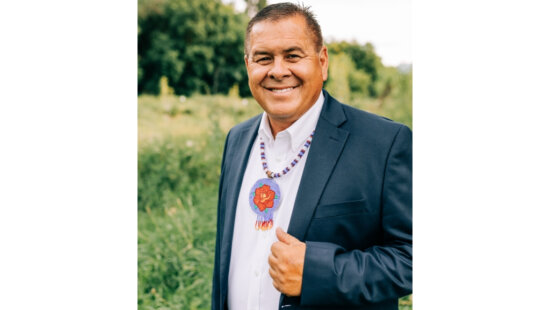

Darren Parry, former chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, shares Indigenous teachings about the land, water, and mountains of Summit County as part of an ongoing TownLift series exploring Native history and perspectives rooted in this region. Photo: Darren Parry

"Where my ancestors once saw a living, breathing world, filled with relatives to be cared for, today many people see property lines, investments, and recreation opportunities. The mountains that once provided spiritual renewal are now covered with vacation homes and ski lifts. The rivers that once carried songs of gratitude now carry the runoff of development."

Darren Parry is the former chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation and a respected Native leader, historian, and educator. He serves on the board of directors for the American West Heritage Center, the Utah State Museum board, and the advisory board of the Huntsman Cancer Institute. Parry is the author of Tending the Sacred: How Indigenous Wisdom Will Save the World and The Bear River Massacre: A Shoshone History. He also teaches at the University of Utah and Utah State University.

TownLift reached out to Darren to better understand the longstanding relationship between the Shoshone people and the land now known as Park City and its surrounding mountains. In this conversation, he shares teachings that continue to live in the land itself, offering guidance for how we might show up with greater care, awareness, and connection.

RB: How did the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone historically understand and interact with the land now called Park City and Summit County, the mountains, rivers, and valleys, as living relatives rather than resources?

DP: The northwestern band of the Shoshone people have always understood the land not as a possession, but as kin, as a living relative deserving of respect, reciprocity, and care. Long before the place was called Park City, our people traveled through those mountain valleys following the rhythms of the seasons. The high meadows, the aspen groves, the rivers that cut through the canyons, all were part of a larger, living family. Each place had a spirit, a story, and a purpose. The mountains offered protection, the streams offered water and fish, the valleys provided grasses for our horses and seeds for our people. Nothing was separate; everything was connected in a web of relationship.

For the Shoshone, land was never something to be owned or extracted from. It was something to enter into relationship with, to listen to, to learn from. When we gathered roots or berries, we offered prayers and gratitude, because those plants were giving their lives so that we might live. When our hunters went into the hills, they knew the elk and deer were also relatives who sustained the circle of life. The landscape around Park City was alive with these relationships, and a place where our ancestors’ footprints and songs are still present if you know how to listen.

Our stories teach that the earth remembers. Every stream remembers the hands that cupped its water, every valley remembers the laughter of children. To the Shoshone, those memories make a place sacred. The mountains of Summit County are not just scenic backdrops; they are our grandparents, standing as ancient witnesses to the passing of generations. The rivers are our veins, the wind our breath. To live well on this land was always to live in balance with it, and to honor the understanding that when we care for the earth, we are in truth caring for our own family.

RB: Are there particular places in the Wasatch or Uinta Mountains that hold deep spiritual or cultural significance for the Shoshone people, and how were those landscapes traditionally honored or cared for?

DP: For the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone, the mountains of the Wasatch and Uinta ranges are more than striking landscapes; they are sacred relatives, places of story and ceremony that hold our memory as a people. Our ancestors moved through these mountains seasonally, but never as mere travelers passing through. We came with reverence. Every ridgeline, every canyon, every stream had its own spirit and its own name in our language. Some places were where we prayed, others where we fasted or sought vision, and others still where the stories of creation were remembered and retold.

One of the teachings of our people is that sacredness is not limited to a single shrine or monument, it lives in the land itself. The high Uintas, with their clear lakes and powerful winds, were places of renewal and ceremony, where a person could go to listen and receive guidance. The Wasatch canyons, rich with water and life, were gathering places for food, medicine, and connection. We understood that caring for these places meant walking lightly, taking only what was needed, and leaving offerings of gratitude, a pinch of tobacco, a prayer, or a song.

Even today, when many of these areas have been developed or renamed, we still regard them as sacred. The old stories tell us that the spirit of a place never leaves, it waits for those who remember. When we return to the mountains, we speak to them as relatives. We tell our young people that when you stand on a ridgeline and feel the wind move through the trees, that is the land speaking back. Honoring these landscapes is not only about preservation; it’s about renewing relationship, and remembering that the earth is alive, that we belong to it, and that our responsibility is to keep that relationship in balance for the generations still to come.

RB: From your perspective, how has the modern relationship to these lands, shaped by recreation, tourism, and development, diverged from or aligned with Indigenous ways of seeing the land as sacred?

DP: From an Indigenous perspective, the modern relationship to the lands around Park City has changed in ways that are both striking and sorrowful. Where my ancestors once saw a living, breathing world, filled with relatives to be cared for, today many people see property lines, investments, and recreation opportunities. The mountains that once provided spiritual renewal are now covered with vacation homes and ski lifts. The rivers that once carried songs of gratitude now carry the runoff of development. It’s not that people don’t love the land anymore, they do, but love without relationship can still be destructive.

In the Shoshone way, we don’t separate ourselves from the land. Our well-being is tied to its well-being. When the earth suffers, we suffer too. Modern society often sees the land as a stage for human activity, something to be used, managed, or conquered. Recreation can bring joy and connection, but it can also bring a kind of forgetfulness, a way of being on the land without truly listening to it. Tourism tends to value the view more than the voice of the place. Development values the potential for profit more than the sacred history under its soil.

Still, I see a quiet shift beginning. More people are starting to understand that the land is not just beautiful, but alive and that it remembers. When hikers pause to give thanks, when conservationists speak of stewardship instead of ownership, that is movement back toward balance. What the Shoshone and other Indigenous peoples have always taught is that the earth does not belong to us; we belong to her. Our task now is to remember that truth, and to bring heart and humility back into our relationship with these mountains and valleys. If we can do that, then perhaps the divide between old ways and new ways will begin to heal.

RB: How do Shoshone teachings about reciprocity and respect for the land continue today, either through ceremony, education, or environmental stewardship in Summit County?

DP: Our Shoshone teachings about reciprocity and respect for the land are not relics of the past, they continue to guide us today in very real ways. Reciprocity means living in balance, giving back for what we take. That teaching is woven into our ceremonies, our stories, and how we raise our children. Even here in Summit County, where so much of the landscape has changed, we continue to return to these teachings through prayer, gatherings, and community education. When we take students or families out on the land, we teach them that every plant, every rock, and every stream has a spirit and that when we gather medicine or food, we offer something back, even if it’s just a few words of gratitude. That simple act of reciprocity keeps the relationship alive.

Through education, we are finding new ways to bring those old teachings forward. I teach my college students and local youth that caring for the earth is not just an environmental issue, it’s a moral and spiritual one. When we plant willows along a river or help restore a wetland, we’re not just healing the land; we’re renewing our kinship with it. These acts of stewardship are our modern forms of ceremony. They carry the same intention our ancestors had: to live with humility and to give more than we take.

The Northwestern Band of the Shoshone has also been involved in projects that restore the land and honor its memory, from Bear River to the high mountain valleys that our people once traveled. Every time we return to these places, we sing, we tell the old stories, and we remind the younger generations that our connection to the land was never broken. It may have been quieted, but it’s still here, in the wind, the water, and the work we do to care for them. As long as we continue to teach and live by these values, the land will continue to recognize us, and we will continue to belong to it.

RB: What might it look like for local residents, visitors, or policymakers in Park City to begin engaging with the land through this Indigenous lens, as kin, not commodity?

DP: If the people of Park City, residents, visitors, and policymakers alike begin to see the land as kin rather than commodity, everything about how they live here would change. They would begin to make decisions not from a place of ownership, but from a place of relationship. To see the land as kin means to ask different questions: not “What can we take?” but “What does this place need from us?” It means remembering that every building, every trail, every development exists within a living ecosystem that has its own spirit, its own memory, and its own right to thrive.

Shared stewardship begins with listening. It means inviting Indigenous voices back into the conversation about how these lands are cared for not as consultants, but as relatives returning home. Policymakers could create space for co-management and for ceremony to happen again on these ancestral lands. Schools and community groups could learn the stories of this place from those who have been connected to it for thousands of years. Even visitors can take part in this by walking with respect, by learning the names of the plants and rivers, by leaving no trace except gratitude.

For the Shoshone people, stewardship was never a program, it was a way of living. You cared for the land because the land cared for you. When you live with that awareness, your choices naturally shift: growth becomes measured, recreation becomes reverence, and conservation becomes kinship. Imagine if Park City saw itself not just as a mountain destination, but as part of a living community that includes the deer, the aspen, and the rivers. That is what shared stewardship could look like; a partnership rooted in humility, gratitude, and belonging.

RB: When you spend time in these mountains now, what do you feel or notice that you wish others could experience, something that connects to the Shoshone understanding of the land as alive?

DP: When I walk in these mountains today, I feel the presence of those who came before me. I can almost hear the quiet songs of my ancestors carried in the wind through the aspen trees. There is a stillness here that speaks, not in words, but in feeling. When I stop and listen long enough, the land begins to remember me, and I remember it. The smell of the sage after rain, the sound of a creek moving over stone, these are the voices of the land reminding me that everything is alive, everything is in relationship.

What I wish others could experience is that sense of belonging; of being part of something much older and wiser than ourselves. Too often people come to these mountains to escape or to conquer, but if they would slow down and truly listen, they might begin to feel what we feel: that the land is not here for our use, but for our connection. The birds, the rivers, the rocks, they all have something to teach, if we approach them with humility.

For the Shoshone people, the land has always been our greatest teacher. It shows us patience, resilience, and generosity. When I’m among these mountains, I feel that teaching still alive. I feel gratitude, and I feel responsibility to care for this living world so that it will continue to speak to our grandchildren as it speaks to me now. That, to me, is the deepest form of prayer: to listen, to learn, and to live in a way that honors the life all around us.

Editor’s Note: This interview is part of an ongoing series exploring Indigenous history, culture, and perspectives in Summit County.