Town & County

How much are short-term rentals like Airbnbs actually cramping Utah’s housing stock?

Homes in North Salt Lake are pictured on Monday, July 15, 2024. Photo: Utah News Dispatch // Spencer Heaps

New report sheds light on surging number of short-term rentals. Statewide, they eat into less than 2% of the market — but they have an outsized impact on vacation areas like Park City, Moab, St. George.

UTAH — There has been a dramatic surge of short-term rental listings in the state, which in 2017 banned cities from prohibiting Utahns from listing their homes on short-term rental websites, according to a study released Wednesday looking at their effect on housing supply and affordability.

While short-term rentals only make up a fraction of the statewide’s total housing stock (less than 2%, according to the report), they are concentrated in ski towns and recreation hotspots like Park City, Moab and St. George, where they have a higher and more disproportionate impact on housing availability and affordability.

Here are some key takeaways from the report released by the University of Utah’s Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute, written by senior research fellow Dejan Eskic and Moira Dillow, a housing, construction, and real estate analyst.

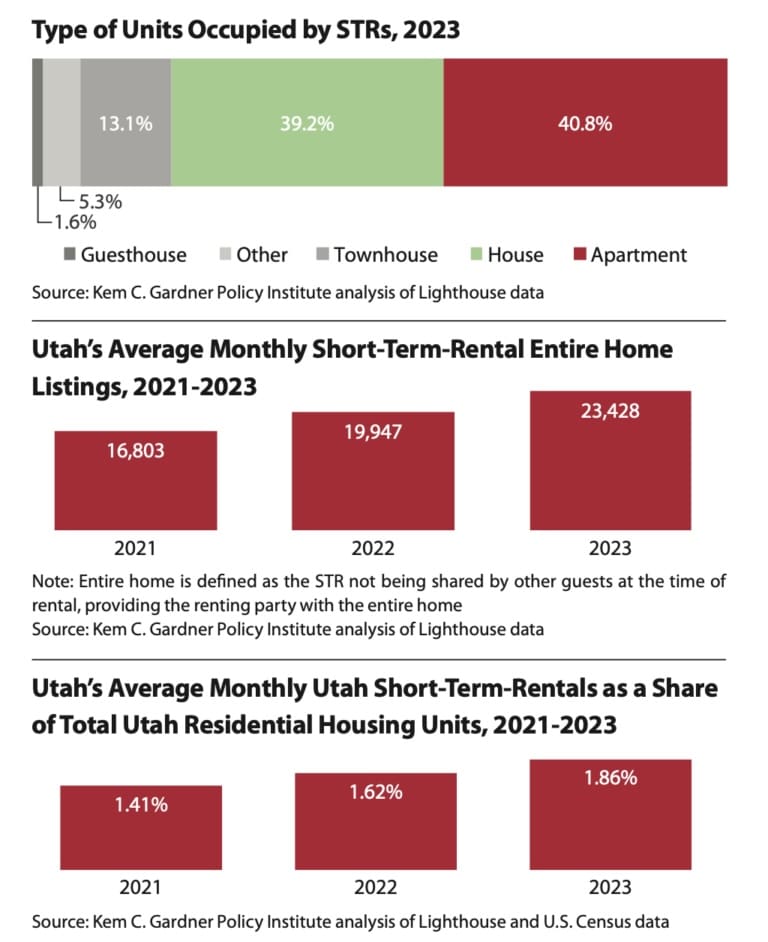

- Rapid growth: The average number of monthly short-term rental listings across Utah has increased more than 39% in just three years, from 16,803 in 2021 to 23,428 in 2023.

- The big picture: Statewide, short-term rental listings account for about 1.9% of all residential units. While this figure is relatively small, it’s been growing — and is expected to continue to grow.

- County concentration: Over 60% of all of Utah’s short-term rental listings are concentrated in three counties: Summit County, Salt Lake County, and Washington County. In 2023, Summit County averaged 6,443 listings per month. Salt Lake County averaged 4,869. Washington County averaged 3,138.

- Areas disproportionately impacted: Summit County — home to the popular and expensive ski town of Park City — has the state’s highest concentration of short-term rentals as a share of the county’s total housing units. In Park City alone, short-term rental listings make up 41.7% of the city’s total share of housing units, while in unincorporated Summit County, they eat up 25.7% of the county’s housing stock. In Grand County (home to Moab and near Arches National Park), short-term rentals consume 18.7% of the area’s housing stock. Compare that to Salt Lake County, where short-term rental listings only make up 1.1% of the county’s total housing units.

- Housing loss: Tourism hotspots like Summit and Grand County are losing existing homes to short-term rentals. From 2022 to 2023 alone, a staggering 14.2 new short-term rental listings came online in Summit County for every 10 new residential units added that year. In Grand County, 10.3 new short-term rental listings came online for every 10 new residential units added.

- Mostly single-family homes and apartments: When breaking down the types of homes short-term rental listings include, nearly 41% are apartment-style units, while more than 39% are single-family homes. About 13% are townhomes.

- Tourism and recreation drives uptick: Tourism — particularly around national parks and ski areas — is a major driver of short-term rentals. In 2023, more than 83% of short-term rental listings were located within 10 miles of a state park, national park or national monument. Almost 25% were located within a quarter mile of a ski resort, and nearly half of all listings were located within 10 miles of a ski area.

- Concentrated in wealthy areas: Short-term rental listings tend to be concentrated in areas with higher housing prices and household incomes, with higher rates of homeownership and a higher number of single-family homes.

As short-term rentals rise in Utah, should lawmakers loosen regulation restrictions?

In 2017, the Utah Legislature passed HB253, which banned cities from prohibiting Utahns from listing their homes on short-term rental websites. Some cities have tried to enact some regulations on AirBnBs and VRBOs, but enforcement can be difficult.

In the years since the passage of HB253, some lawmakers have contemplated changes to Utah’s short-term rental laws — some to allow more restrictions and others for more leniency — but lawmakers have not yet landed on exactly what to do about the growing number of short-term rentals in their state.

This year, at least one legislator, Rep. Neil Walter, R-St. George, has said he intends to run a bill to re-evaluate what he called in an August interim meeting the “Knotwell Rule,” referring to HB253 by using the name of its sponsor at the time, Rep. John Knotwell.

“One of the things that is impacting housing supply in our state is short-term rentals,” Walter said in that August Political Subdivisions Interim Committee meeting, adding that in his home county of Washington County, “there are 1,000 homes that are estimated by St. George city to be rented for short-term rentals that do not meet their zoning, but they don’t have the ability to enforce that zoning because essentially the Knotwell Rule.”

Estimates included in the Kem C. Gardner report are even higher for St. George, ranking that city as fourth highest for total number of short-term rentals, with an estimated 1,277 homes listed in 2023. However, according to the report, that makes up less than 3% of that city’s housing stock. Washington County as a whole had about 3,715 listings in 2023, eating up about 4.3% of its housing stock.

Walter’s bill hasn’t yet been made public, so it’s not yet clear what his legislation will entail. But he characterized short-term rental regulation as a “really important local control issue,” to allow cities to “be able to enforce their zoning.”

“If St. George feels like it’s impacting their housing supply, then the municipality can take action and enforce their zoning in a different way that would increase their housing supply,” Walter said. “I think it’s an important aspect of this particular discussion to reconsider that legislation.”

Will allowing more regulation of short-term rentals actually make a difference, though?

Eskic told reporters during a media availability on Wednesday it’s important to recognize that short-term rentals are only a fraction of the statewide housing affordability problem — though he acknowledged they do impact some communities more than others.

“When we look at what’s impacting housing, short-term rentals are a piece of it, but it’s not the main piece, right?” Eskic said. “There is no main piece. There are so many obstacles for housing affordability. Short-term rental is just one, one smaller piece of that.”

Eskic noted that even if all short-term rentals were banned across the state, “we’d still have a housing shortage,” which housing experts largely attribute to Utah’s rising housing costs because supply has long lagged behind demand, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, its remote work opportunities and low interest rates fueled a rush on the housing market.

“When we look at where short-term rentals are, they’re not necessarily in the highest growth areas in our state, just tourism-heavy areas,” Eskic said. “(If you) ban short-term rentals in Summit County tomorrow, are you going to see a lot of people occupy those housing (units)? A lot of those housing that are short-term rentals are likely second homes to begin with. … So are they going to make an impact on the supply? It’s unlikely.”

Eskic also pointed to New York City, which recently passed an aggressive ban on Airbnbs. “All it’s done,” he said, “is shoot up their hotel prices. It’s not yet made an impact on affordability, and I don’t think it will, because it’s New York City.”

Eskic said if policy makers do consider changes to Utah laws when it comes to short-term rentals, they should probably consider policies that would be more tailored to communities that are more impacted than others.

“If we do a blanket state policy, I don’t think it’s going to create much impact on affordability statewide,” he said. He again pointed to Summit County — home to Utah’s most expensive zip codes — and said even all short-term rentals there were released for sale, “they’re still going to be (listed at) Summit County prices.”

When asked how policy makers can balance the pros and cons of short-term rentals’ economic impacts, Eskic said, “That’s a really hard question to answer.” But, he said policy makers should consider the “gaps in housing affordability” in tourist hotspots, which typically struggle to maintain enough workforce housing for people in service industries including retail, hospitality and restaurants.

“This isn’t an issue everywhere,” he stressed. “It’s an issue in some communities.”

Written by Katie McKellar, Utah News Dispatch