Neighbors Magazines

Dam it, and they will come: The beaver’s role in Utah’s environmental health

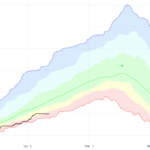

Beaver dam analogs (BDAs) in Kimball. Photo: Marshall Wolf

How could beavers be better at building dams than human beings? That was among the surprising takeaways from biologist Marshall Wolf’s 152-page dissertation, published in December 2023. Wolf, who completed his Ph.D. at Utah State University, built artificial beaver dams in Park City’s Swaner Preserve & EcoCenter and compared them to the real beaver-made deal between 2019 and 2021.

Why a researcher would do this is a story about our local “living laboratory,” as Rhea Cone, director of conservation at Swaner, calls the 1,200 acres of protected wetland. It is also a story about why if we build it, they will come—only instead of dead baseball legends and Kevin Costner, it’s 60-pound rodents and scientists.

For nearly 200 years, a beaver in Utah was either a felt hat-to-be or a pest to be dislodged. Today, scientists consider the beaver crucial to preserving, restoring, and maintaining wetlands that clean our water, sequester carbon, and absorb snow runoff before it floods our home—all free of charge.

Castor canadensis, the American beaver, is an ecosystem engineer. Its dams trap water in ponds, forming habitats for wildlife and minimizing erosion. Beaver infrastructure also raises the water table, nourishing willows and cottonwoods.

When Wolf first visited Swaner in 2018, he observed beaver activity around Swaner but not in it. “The thing that jumped out right away was the lack of building material or woody riparian vegetation to support beavers,” Wolf says.

Bringing beavers back to a wetland like Swaner is a chicken-and-the-egg problem. Without “woody riparian” species like willows and cottonwoods, beavers lack the food and building materials to sustain themselves. And, without beavers maintaining the water table, there aren’t enough willows and cottonwoods to entice beaver colonizers.

When European fur trappers first arrived in what would become Park City in the early 1800s, wetlands stretched from Kimball Junction to Main Street. The newcomers turned the dense beaver population into lucrative pelts.

The combination of eradicating beavers and urbanizing Park City altered the wetlands. Without dam-made pools, aquatic habitats vanished. Water moved faster, cutting the streams increasingly deeper, while human beings diverted more and more water for their use. The willow and cottonwood roots could no longer reach the water table, so they mostly died off by the 1990s. The surrounding floodplains dried out, leaving the grassy expanses seen today.

The drier, treeless, beaver-less Swaner offered a natural experiment. If Wolf built beaver dam analogs, known as BDAs, could they revive the Swaner ecosystem enough to make beavers return? Could BDAs be a “restoration prescription,” as Wolf puts it? Cone, who manages research at Swaner, was keen to help Wolf find out.

To build dams, Wolf, Cone, and their collaborators pounded wooden posts into streambeds, leaving three to four feet of wood above ground. They then used onsite vegetation, rocks, sediments, and soil to weave a dam-like structure through the posts. Sturdy wooden posts aren’t naturally available at Swaner, but Wolf and Cone had access to about 10,000 cubic meters of discarded Christmas trees collected by Park City Lacrosse in its annual fundraiser.

Wolf’s research illustrates that BDAs are significantly better for wetlands than the control—no dam at all—but beaver-made versions are still better at restoring wetlands. Human beings have engineered marvels ranging from the ancient pyramids and modern skyscrapers to the iPotty and dogbrella, but we can’t best a rodent using its front teeth.

“It just comes down to work hours,” says Wolf. “The beavers are putting in a lot more. And they’re also doing a couple of things that no one has been able to replicate.”

For example, beavers dig canals that channel water onto the floodplain, inundating the soil. They use the resulting mud to make their dam watertight.

Wolf’s “restoration prescription” appears to be working. Over the last five years, beavers have begun to recolonize Swaner voluntarily. There are at least four active beaver lodges, including one just off the deck at Swaner EcoCenter. Beavers have even colonized the BDAs, effectively choosing a free, semi-furnished home.

Wolf, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Columbia River Intertribal Fish Commission, continues to shape our ecosystem. His research secured a Park City Community Foundation grant, which funded the creation of nearly 100 BDAs in the Preserve. Every fall, volunteers with Swaner, the nonprofit Sageland Collaborative, and Basin Recreation perform maintenance on the BDAs.

As a living laboratory, Swaner changes in response to the research conducted within it. The return of beavers means that future researchers might work in an entirely different laboratory. Hopefully, it’s one with richer wildlife, higher water tables, and abundant willows and cottonwoods that enable beavers to build their own dams—to the benefit of their freeloading neighbors—including us.