News

Conservationists question need for Iron County groundwater pipeline

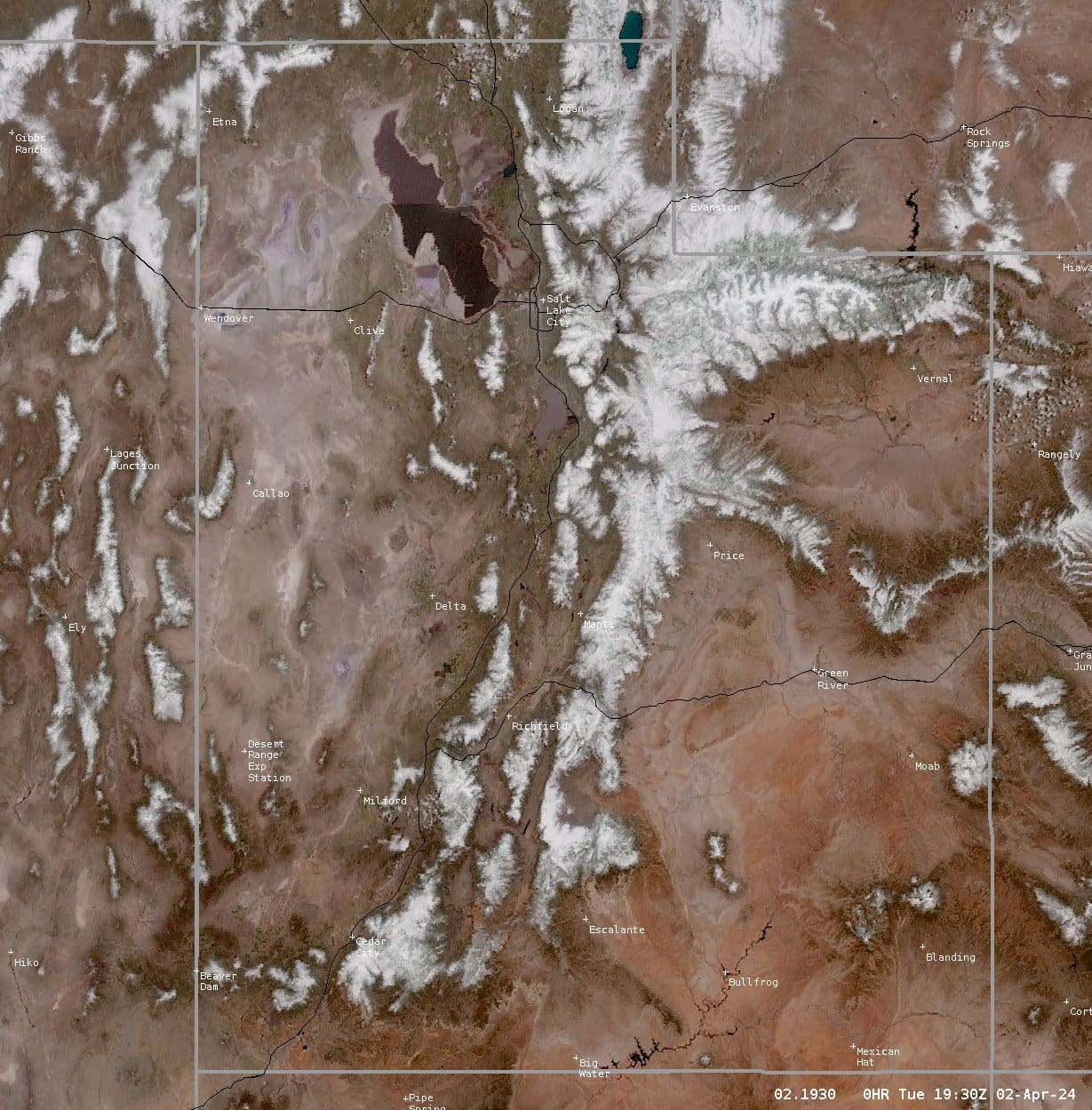

Cedar City is the largest municipality in Iron County. The city's population grew over 22% between the 2010 and 2020 U.S. Census. Photo: Cedar City, Utah

SALT LAKE CITY — A coalition of water conservation groups that opposes plans to pipe groundwater out of a valley near the Utah-Nevada line contends that southern Utah water officials are artificially inflating the need for additional supply to justify spending hundreds of millions on a pipeline.

In order to prepare for population growth in southern Utah’s Cedar Valley, officials from the Central Iron County Water Conservancy District want to spend roughly $260 million to construct about 70 miles (113 kilometers) of buried pipes to transport water from an aquifer that sits below the Pine Valley. They argue limits on their local groundwater supply and an influx of new residents require they diversify their water supply to prepare for the future.

The project has long been opposed by neighboring Beaver County, Native Americans including the Indian Peaks Band of the Paiute Tribe of Utah, and Nevada counties worried siphoning water from Pine Valley will affect nearby aquifers.

Analysis published on Wednesday by the Great Basin Water Network, Utah Rivers Council and Iron County Water Conservatives suggests that the district is overestimating future demand. Representatives of the groups suggest expanding conservation measures would be more cost-effective water management than building the pipeline.

“The reason that future water demand matters, of course, is because it’s future government spending,” said Zach Frankel, the Executive Director of the Utah Rivers Council.

Frankel argues that modest conservation could render the pipeline unneeded and avoid charging ratepayers and taxpayers for it.

He and other researchers also question the water district’s 2020 management plan because it uses figures published in 2012 by the University of Utah’s Kem Gardner Policy Institute. Those decade-old figures project Iron County’s population will reach 154,000 by 2070. However, last month, the institute analyzed new census data and projected the population will only grow to 105,000, 46% less than projected a decade ago.

The district calculates future water demand by multiplying projected population by water consumption per capita. The conservationists argue that in Iron County, where agriculture — primarily alfalfa growers — uses 75% of water, the conversion of farmland into subdivisions “almost always frees up significant quantities of surplus water.”

“It has been well established that as population increases, agricultural water use decreases. This occurs because as populations grow, they expand outward from urban centers, turning agricultural lands into strip malls, subdivisions, parking lots, and other less-water intensive landscapes,” they write in the report.

Paul Monroe, the General Manager of the Central Iron County Water Conservancy District, said the Cedar City area had historically outpaced growth projections from the state and Gardner Institute. However as the project moves through environmental impact review and federal approval processes, the district may add in the updated figures, he said.

He said the current supply wouldn’t suffice because of limits put in place to protect the Cedar Valley aquifer and ensure it can recharge amid drought.

“We need additional supply for the current residents that are here, as well as those that are coming in the future,” Monroe said.