Environment

Corridors, not borders: Summit County’s Indigenous pathways

Winter Pathway Photo: TownLift

If there is one story I hope Park City and Summit County residents carry in their bodies, it is this: you are living in a place built from relationships. The freeway you drive, the ski run you descend, the bike path you follow, each echo routes that sustained families for centuries.

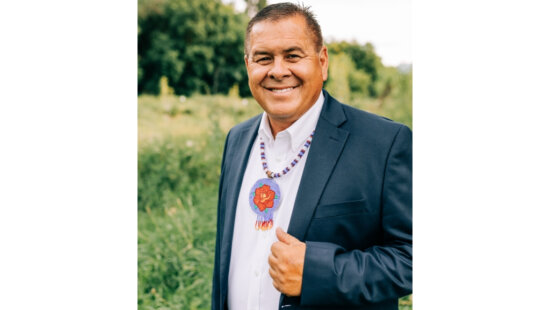

Darren Parry is the former chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation and a respected Native leader, historian, and educator. He serves on the board of directors for the American West Heritage Center, the Utah State Museum board, and the advisory board of the Huntsman Cancer Institute. Parry is the author of Tending the Sacred: How Indigenous Wisdom Will Save the World and The Bear River Massacre: A Shoshone History. He also teaches at the University of Utah and Utah State University.

TownLift reached out to Darren to better understand the longstanding relationship between the Shoshone people and the land now known as Park City and its surrounding mountains. In this conversation, he shares teachings that continue to live in the land itself, offering guidance for how we might show up with greater care, awareness, and connection.

TownLift reached out to Darren to better understand the longstanding relationship between the Shoshone people and the land now known as Park City and its surrounding mountains. In this conversation, he shares teachings that continue to live in the land itself, offering guidance for how we might show up with greater care, awareness, and connection.

When TownLift asked Parry to describe Summit County’s role as an early travel and trade corridor, Parry pointed to an older map—one written in passageways and seasons:

DP: If you could peel back the asphalt and ski lifts, and if you could lay your hand on this land the way our ancestors did, you’d see that Summit County was once less a destination and more of a living passageway.

Long before Park City became a place people arrived at, it was a place people traveled through. The mountains were never barriers. They were backbones that held ancient trails, braided like rivers across the spine of Utah.

From the north, a well-worn corridor ran the length of present-day Park City and down through Parleys Canyon into the Salt Lake Valley. Another route dropped south and east through Heber, and then curved toward the Uinta Basin, where the rivers opened into fertile grounds. And further east, beyond Kamas, trails lifted toward the high Uintas and Wyoming.

These were not narrow footpaths; they were seasonal arteries.

In wet months, people moved along higher ridges where mud could not swallow moccasins. In winter, they followed the valleys where snow packed hard and game sheltered low.

Movement itself was a relationship with weather, with water, with the pulse of the seasons. This place was a meeting ground for the Great Basin peoples, like the Shoshone, Goshute, Paiute, Ute, and at times even the Blackfoot from farther north. The trails threaded together worlds: sagebrush basins and tall-grass plains, salmon-rich rivers and bison country.

To speak of “connection” is too soft a word. These routes were the nerves of a living landscape.

Along them traveled families, traders, diplomats, dreamers that carried obsidian, pine nuts, medicinal plants, stories, songs, and sometimes just news of who had been born, who had passed on, and who was seeking alliance.

Trade was the only purpose. Marriages tied people together across territories, creating kinship far beyond political borders. A Shoshone youth might marry into a Ute family, and suddenly a mountain pass was no longer just geography; it was the pathway to your in-laws, to your responsibilities, to the people who would feed you when times were lean. Diplomacy was not an abstract idea; it was lived through visits, shared meals, and children raised between cultures.

In this way, peace was not the absence of conflict; it was the very presence of relationships.

Travel had etiquette. No one simply wandered into another’s homeland without care. When approaching a camp or crossing unfamiliar territory, our people announced themselves with song or with a small offering — a handful of sage, a carved token, a skin, something acknowledging: I see you; I honor you; I come with respect. Guests were expected to behave honorably, and hosts responded with generosity when that respect was shown.

If conflict arose, it was often resolved through counsel, not quick judgment, but long listening.

Gifts were exchanged to rebalance the world, not as payment, but as a promise.

Certain places in Summit County were known as the kind of spots where travelers reliably met, not by appointment, but by the natural magnetism of geography. High meadow saddles, river confluences, warm springs tucked against rock. These were crossroads, council grounds, safe places to camp and wait for others on the trail.

Even today, if you stand at the mouth of Parleys Canyon or look across the open meadows above Kamas, you can feel the old gatherings beneath your feet, and you can almost imagine the way stories would rise with the smoke of evening fires, how decisions for whole regions were once

made in the shadow of these mountains.

Our modern maps draw trails like lines of separation, boundaries, borders, and edges. But our ancestors experienced them as the opposite: not lines that divide, but threads that tie people and places together. A trail is a promise that someone walked before you, and that someone made the trails for us to follow, and someone will walk after.

It is memory pressed into the earth. It was always an invitation.

If there is one story I hope Park City and Summit County residents carry in their bodies, it is this: you are living in a place built from relationships. The freeway you drive, the ski run you descend, the bike path you follow, each echo routes that sustained families for centuries.

When you walk this land with awareness, you join an old and ongoing movement. You step into kinship, with people, yes, but also with soil and snow and the patient mountains that have watched us come and go.

We often think that history is old and buried. But here, in these passes and valleys, it still speaks.

All we need to do is listen.

Editor’s Note: This interview is part of an ongoing series exploring Indigenous history, culture, and perspectives in Summit County.