Environment

‘We’re All Connected’: How the Great Salt Lake shapes life in Summit County

A bison standing on top of a grass covered hill at the Great Salt Lake. Photo: Photo by Harrison Steen

PARK CITY, Utah — As Utah lawmakers work to manage the Great Salt Lake’s salinity by raising the berm that separates its two arms, scientists warn that the lake’s ecology—and the state’s air quality—remain in crisis.

Dr. Bonnie Baxter, a professor of biology and the director of the Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster University, emphasizes that the solution begins far from the shoreline. “The key to solving our problems is keeping water in the lake,” Baxter said. “To ensure as much water as possible flows into the lake, we must focus on the entire watershed. Overusing water during the hot, dry summer is not a smart strategy in any desert biome, even one that includes mountain communities.”

Baxter, who studies the microorganisms that inhabit the lake, pointed out that residents of Summit County have a direct impact on its health. “Because Summit County is upstream, any pollution from your water system will eventually reach the Great Salt Lake,” she explained. “We are all connected by our watershed. It’s simply not true to think that because you are upstream, you don’t have a responsibility.”

Toxic Legacy Beneath the Surface

The Great Salt Lake, a remnant of prehistoric Lake Bonneville, has become a sink for both natural and human-made contaminants. According to Baxter, arsenic naturally erodes into the basin from western mountain systems, while historical gold mining has released mercury, which settled into the lakebed. “We have the highest mercury pollution problem west of the Mississippi,” she noted. “The organisms in the lake convert that mercury into its organic form—the type that can bind to tissues and move up the food chain.”

This process magnifies toxicity throughout the ecosystem; “The flies concentrate it, and then the ducks that eat them further concentrate it,” Baxter explained. “We are the only location with mercury warnings for ducks instead of fish.” Other contaminants include selenium from copper mining and pharmaceuticals flushed downstream. “While the streams that flow into the lake are protected by the Clean Water Act, the lake itself is not,” Baxter added. Recent research has found that the lake’s birds are also carrying microplastics and “forever chemicals.” As a result, duck hunters have begun discussing the need to avoid consuming their game, particularly in relation to children and pregnant women, due to these pollutants.

Policy Shifts and Biological Consequences

In October, the Utah Legislature passed HB1001, granting the Division of Forestry, Fire, and State Lands the authority to raise the Great Salt Lake berm up to 4,192 feet to manage salinity. Supporters argue that this change will help prevent salinity spikes in the southern arm, while critics warn it might isolate the northern arm and worsen dust exposure.

Baxter, who serves on the state’s Salinity Advisory Committee, notes that while the adjustment will help stabilize brine shrimp and brine fly populations, it is not a long-term solution. “Managing salinity spikes is valuable for emergencies—we can respond quickly,” she stated. “But to truly preserve this ecosystem for both the migratory birds and the humans who live here, we need to bring more water to the lake.”

Airborne Warnings

Although Baxter does not study air quality directly, she pointed out that the exposed sediments of the lakebed contain heavy metals and toxic compounds that can travel well beyond the Wasatch Front. “The airborne distribution of heavy metals and dust from the lake bed extends far beyond the Wasatch Front,” she explained. “From what I understand, these dust storms can be detected as far away as Wyoming, indicating that Summit County is not immune.”

The Washington Post reported that dozens of dust events occur each year across the once-water-covered 120-square-mile area, some of which carry arsenic and other carcinogenic metals.

Shared Waters, Shared Fate

For Summit County residents who may feel removed from the Great Salt Lake crisis, Baxter offers a reminder: the region’s snowpack, streams, and air are all part of the same interconnected system. “The birds that ingest the mercury-laden flies have wings,” she said. “They fly and can spread heavy metals to other ecosystems. Ultimately, we are all connected.”

Local land protection efforts align closely with statewide salinity management. While state agencies work to stabilize the lake’s brine ecosystem by adjusting the berm, upstream conservation—from riverbanks to rangelands—helps retain water and reduce pollution before it reaches the terminal lake.

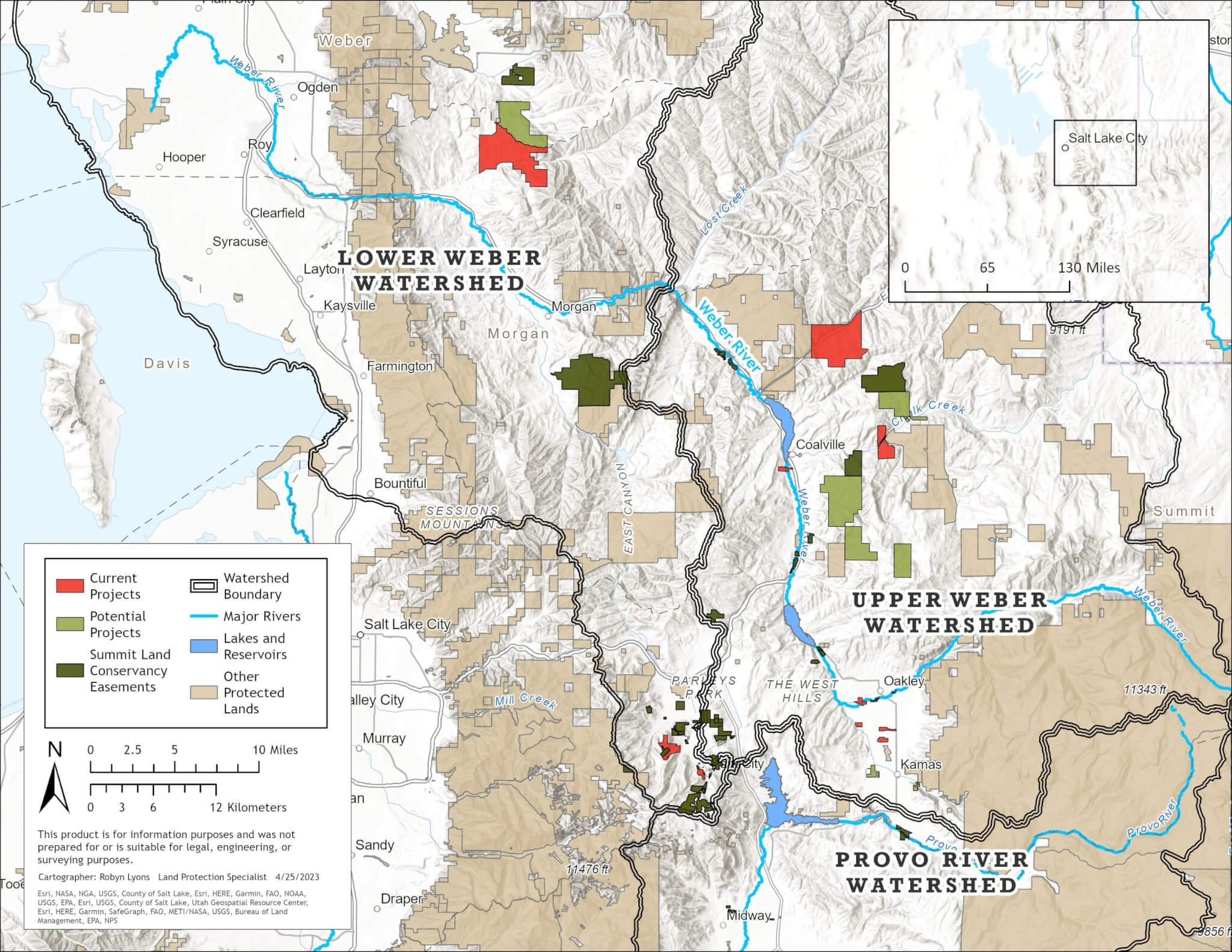

Through its Utah Headwaters Initiative, the Summit Land Conservancy is addressing this critical upstream link. The initiative focuses on protecting lands within the headwaters of the Weber, Provo, and Bear river systems—the very rivers that feed the Great Salt Lake. Its goal is to triple the number of protected acres within five years, using a revolving “Quick Strike” fund to secure key landscapes while longer-term financing is arranged.

By conserving riparian corridors and managing working lands across the Wasatch Back, the initiative helps keep water on the landscape. These measures improve groundwater recharge, filter pollutants, reduce habitat fragmentation, and ensure that cleaner water continues to flow downstream—ultimately suporting the Great Salt Lake.

Urgency and Hope

Despite the challenges, Baxter expressed that she feels more hopeful than she has in years. “What gives me hope is that we are all on the same page,” she said. “The governor has committed to restoring the lake to a healthy level by the time of the Olympics. The legislature, state agencies, and scientists alike all want the same outcome.”

However, she cautioned that the timeline is critical. “What worries me is that we may have waited too long. If nature doesn’t support us during this period, we could struggle to overcome significant obstacles due to our delayed action.”

Her advice for residents, both in Summit County and beyond, is straightforward: stay engaged. “Utah residents have made a real difference by speaking with their representatives,” Baxter observed. “I’ve seen the power of this engagement. When people raise their voices, whether through science, writing, or poetry, they can have an impact.”