History

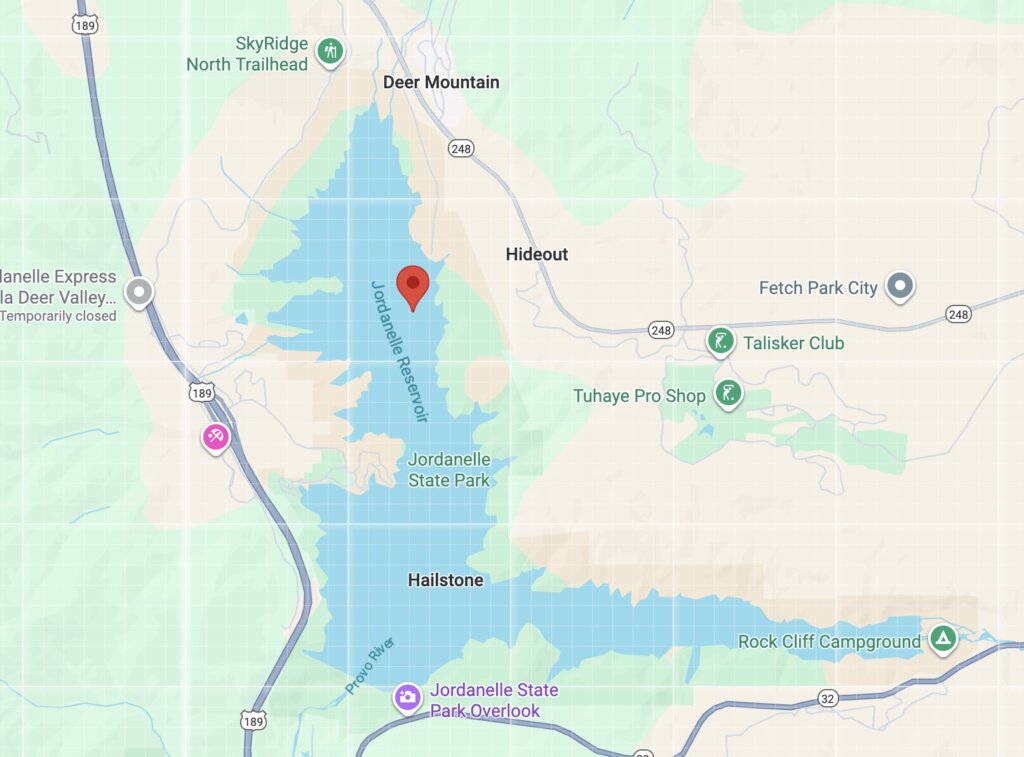

Keetley, Utah: The sunken town below Deer Valley’s historic ski resort expansion

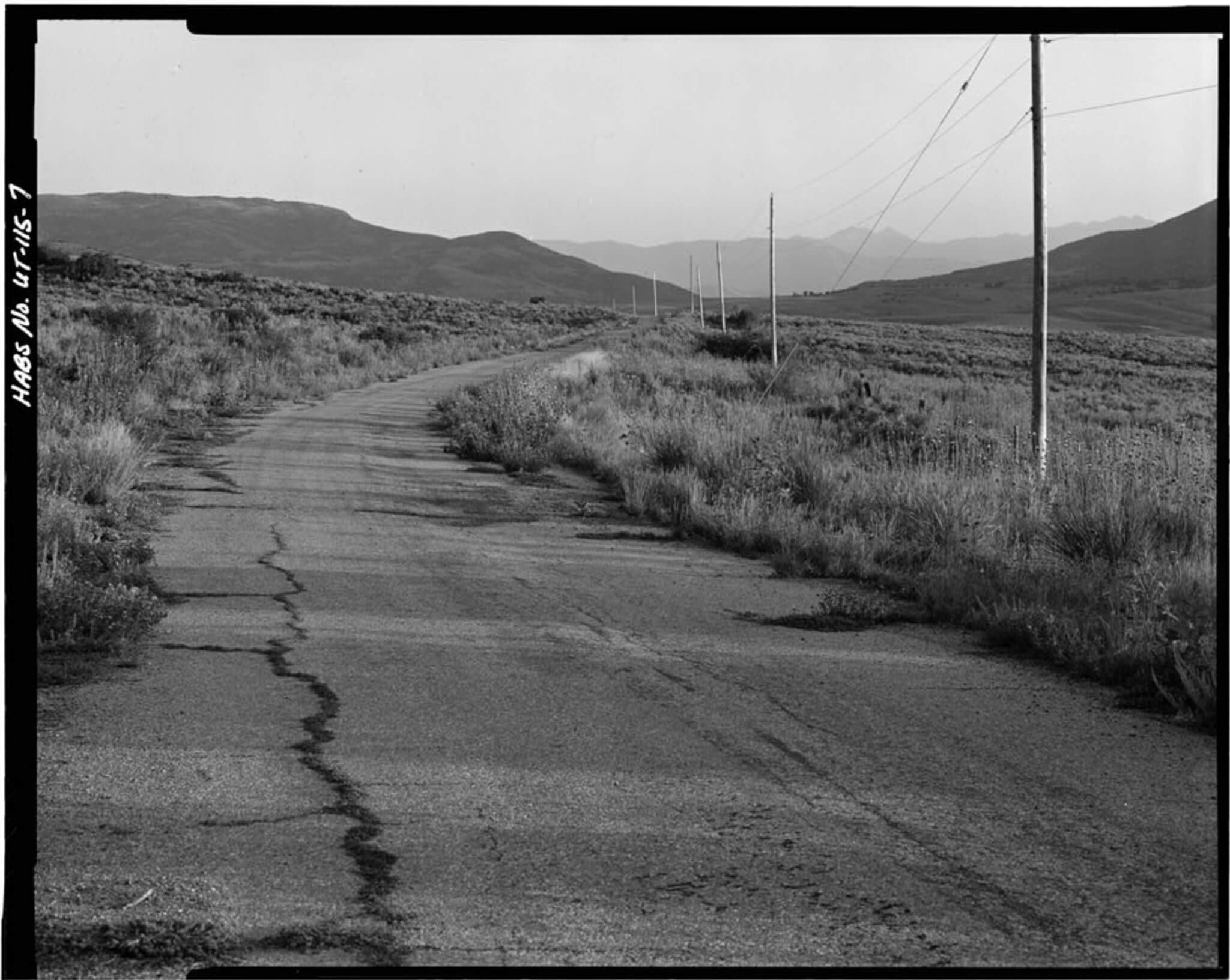

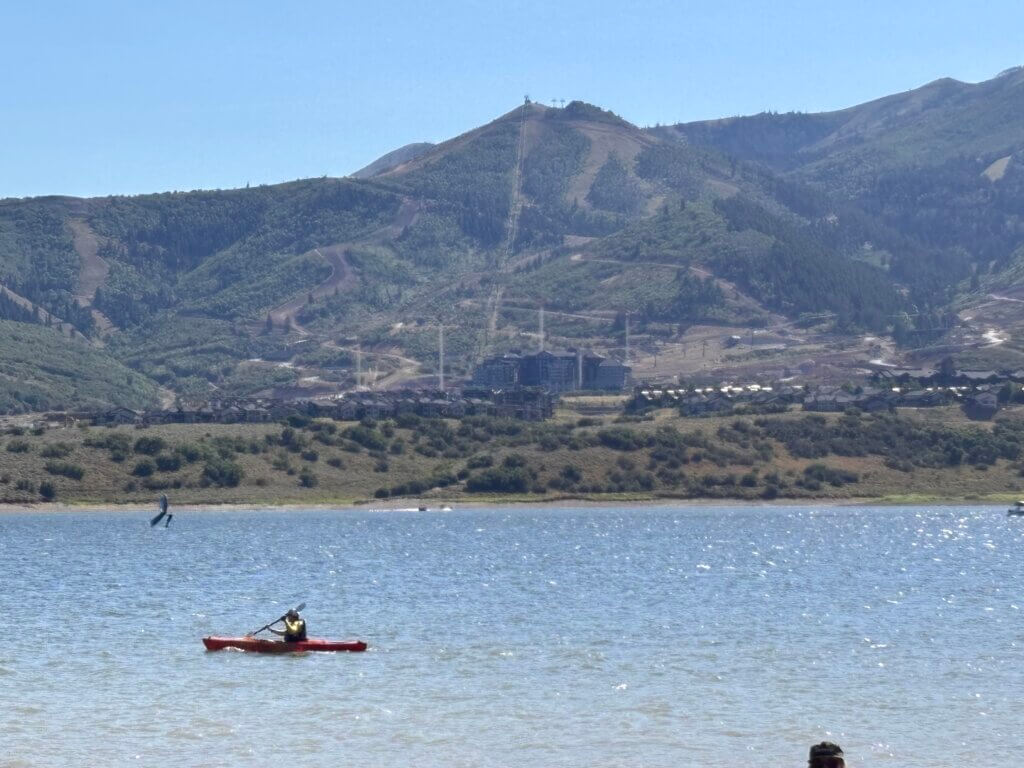

Where pavement meets water—this was once the main road to Keetley, now submerged beneath Jordanelle Reservoir. Photo: TownLift.

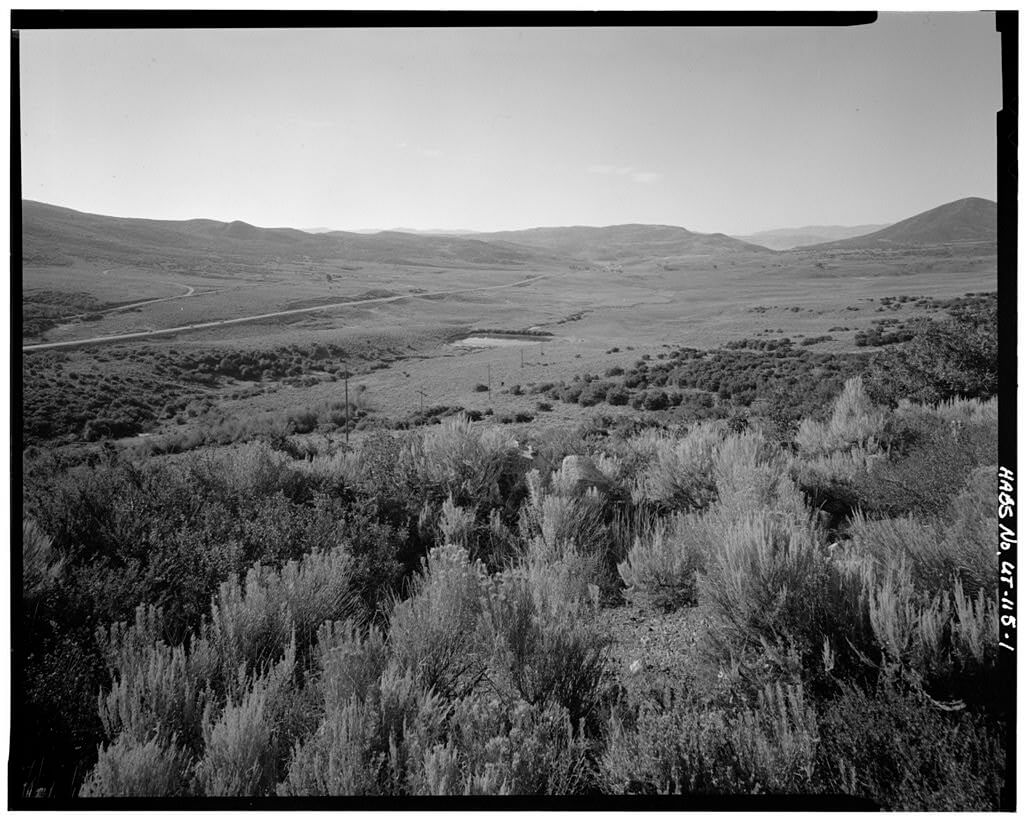

Beneath 5.1 square miles of water lie the submerged remains of over a century of human endeavor: the Ontario mine shafts, the empty miners' quarters, the ruins of the Blue Goose saloon, and Fred Wada's agricultural fields.

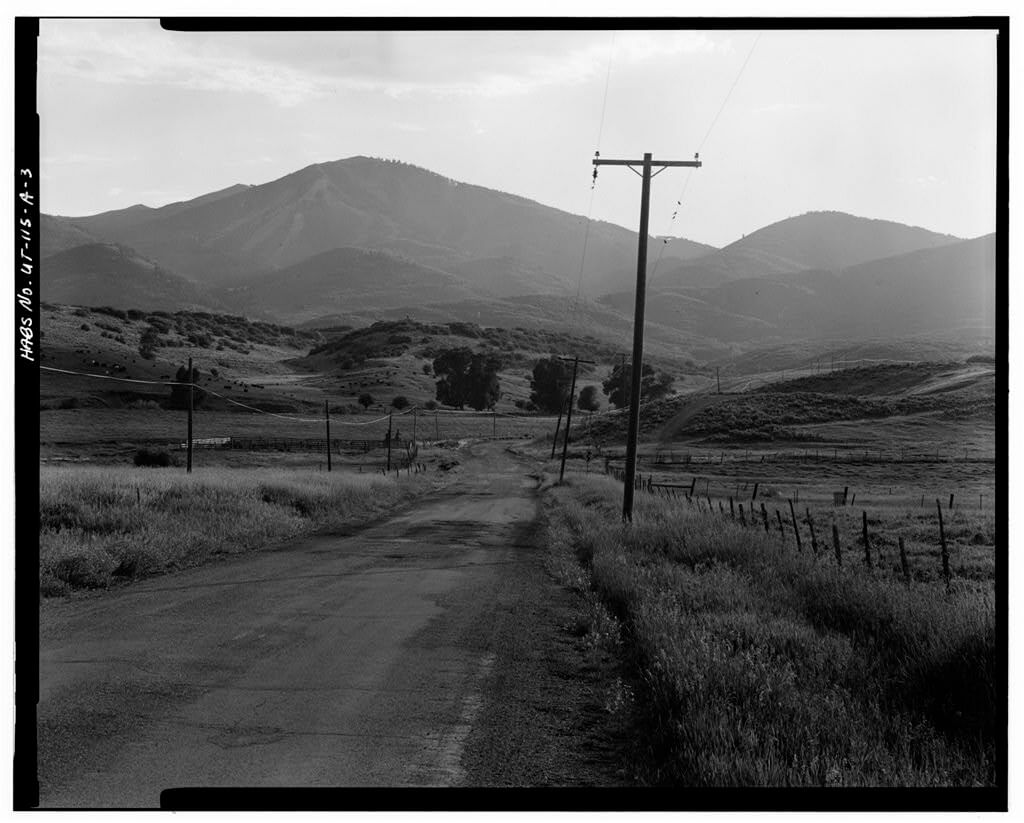

WASATCH COUNTY, Utah — Today, boaters and water sports enthusiasts enjoy the waters of Jordanelle Reservoir, a 5.1-square-mile lake. Few realize, however, that beneath their boats and boards lies Utah’s own subdued Atlantis, the submerged remains of Keetley (and Elkhorn/Hailstone), a once-thriving mining town with an impressive history spanning over a century. And sometimes in years where the water levels are low, the old road to Keetley peeks out and reminds us that it’s still there.

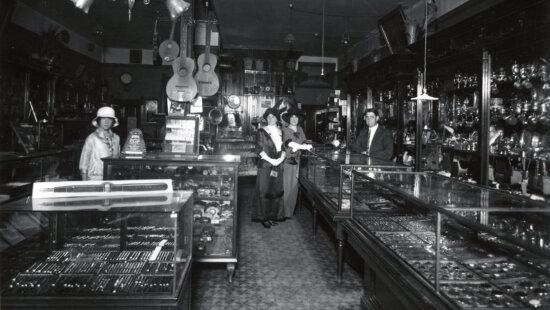

Like most towns in Summit and Wasatch Counties, Keetley’s story begins with the silver boom. After silver was discovered in Park City, prospectors opened the Ontario claim in 1872. The settlement that emerged was named after John “Jack” Keetley, a former Pony Express rider who supervised the construction of the crucial Ontario Drain Tunnel No. 2.

The town was established between 1887 and 1894 to house the miners working on this ambitious tunneling project aimed at draining the groundwater out of the mines.

The operation proved highly successful. By 1921, Park Utah Consolidated Mining Company was paying its first dividends, with stock reaching $6 per share the following year after distributing $250,000 in dividends (about $4.5 million today). About 150 miners were producing 200 tons of ore daily, with the lowest assays showing an impressive 80 ounces of silver per ton.

As mining operations expanded, so did Keetley. The entire area was eventually purchased by brothers George and Donald Fisher, who developed it for both mining and ranching. During the 1920s boom, the Fishers constructed numerous two-story buildings that could house up to 600 miners, creating a substantial community.

The town had all the amenities of a thriving settlement: homes, modern offices, a schoolhouse, a general store, and a railroad spur built by the Union Pacific at a cost exceeding $400,000. The social center of town was the Blue Goose, an amusement hall operated by brothers known as Big and Little Joe. This establishment hosted boxing matches and dance nights, featured pool tables and a marble-topped bar, and allegedly operated a bootlegging operation during Prohibition.

The Great Depression brought an abrupt end to Keetley’s mining prosperity. As Utah’s mining operations stalled, the town was largely abandoned, its buildings standing empty in the mountain valley. However, Keetley would find new life during World War II in an unexpected way.

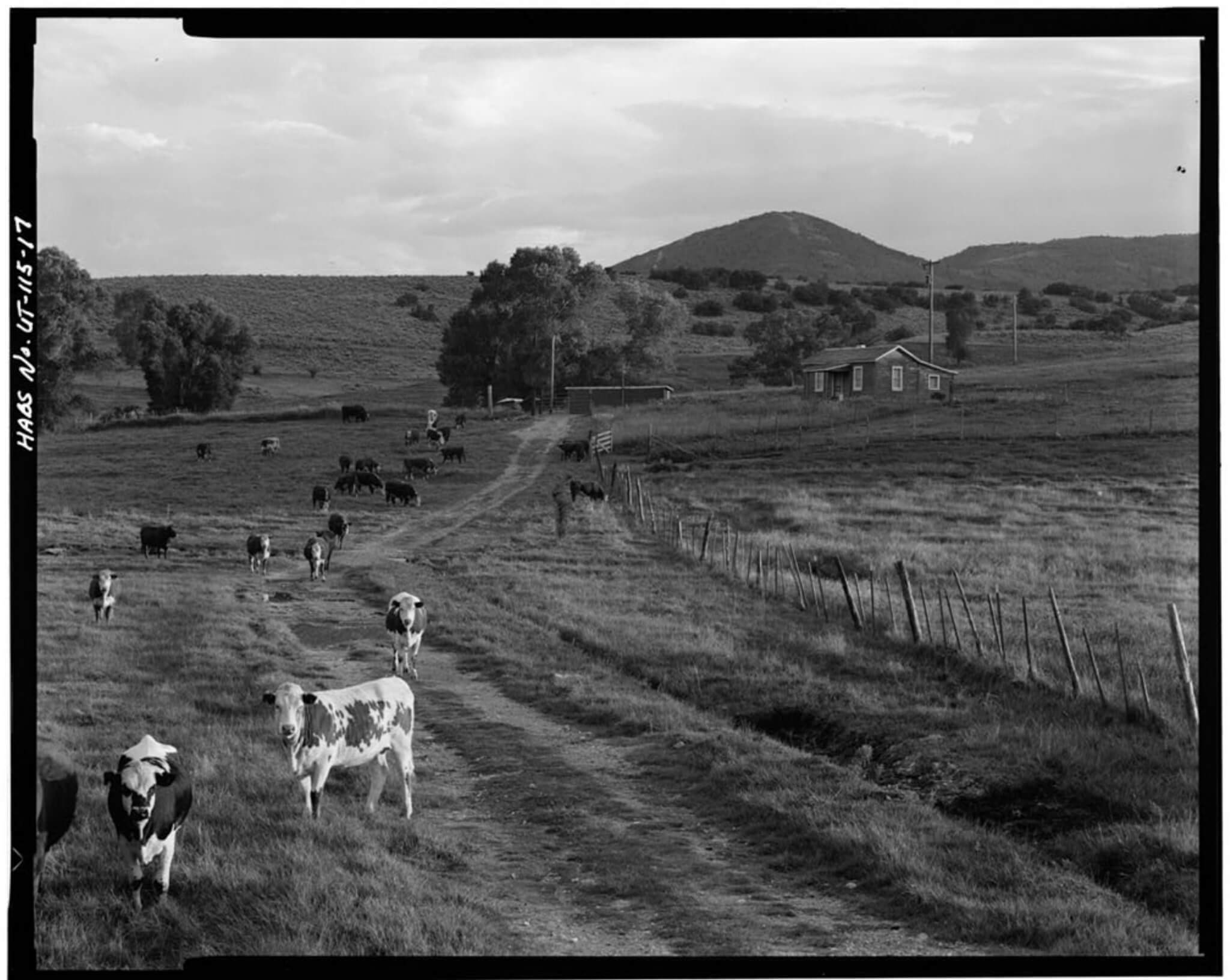

In 1942, one of the Fisher brothers leased the land to Fred Wada, a Japanese-American businessman who established an agricultural cooperative. This farm co-op served as an alternative to internment camps for Japanese-American citizens, such as the facility outside Delta, Utah. Despite opposition from the Park City Town Council and local sheriff, who lobbied for the removal of the co-op, Utah Governor Herbert Maw praised the Keetley farmers, calling them “loyal high-class citizens” after sampling their produce.

Wada’s agricultural operation breathed new life into the abandoned mining town, with Japanese-American families working the fertile valley floor to produce crops during the war years.

As Utah’s population grew in the post-war era, the need for reliable water supplies became increasingly urgent. Planners identified the Jordanelle valley as an ideal location for a reservoir to serve Wasatch County’s expanding communities. The site’s geography and proximity to existing infrastructure made it perfect for water storage, even though it meant the end of the historic community.

In 1995, the dam gates closed for the final time, and water began rising in the valley. As one historian poignantly observed, “when the [Jordanelle Reservoir] is filled and all the recreational facilities in use, people are not likely to remember… the small town [of Keetley]… far below them in its watery grave.”

Beneath 5.1 square miles of mountain water lie the submerged remains of over a century of human endeavor: the Ontario mine shafts, the empty miners’ quarters, the ruins of the Blue Goose saloon, and Fred Wada’s agricultural fields. The Jordanelle Reservoir now serves its intended purpose, providing water storage for Utah’s growing population while offering recreational opportunities through Jordanelle State Park.

The recommended master plan for the state park included the Hailstone (formerly Elkhorn) recreation area on the west shore, designed to accommodate both water and non-water activities for Utah residents and out-of-state visitors. The reservoir’s surface fluctuates significantly based on seasonal water needs, storing water during wet periods for release during dry ones—a cycle that would have been familiar to the miners and farmers who once called this valley home.

Supporting the largest ski resort expansion in history at Deer Valley

Today, the Jordanelle Reservoir continues to shape development in the area. Water for the East Village expansion is being supplied through an agreement with the Jordanelle Special Service District, drawing from the Provo River and the Ontario Drain tunnel. The reservoir will also play a critical role in recapturing 80% of the water used in the state-of-the-art snowmaking facility.

According to Snowmaking Manager Brett Hawksford, the system includes 1,200 snow guns, 350,000 feet of pipeline, three new pump houses, and a new 10-million-gallon snowmaking pond. It’s designed specifically to provide consistent snow coverage across the new terrain, which lies mostly under 7,700 feet in elevation and includes many south- and east-facing slopes—conditions less favorable for natural snow retention.

This modern water management demonstrates how the reservoir system that claimed Keetley continues to serve the region’s evolving needs—from municipal water supply to recreational snowmaking—ensuring that the sacrifice of the historic mining town serves multiple generations and purposes.

Sources:

- Dalton Gackle, “Images of America, Park City”

- George A. Thompson and Fraser Buck, “Treasure Mountain Home”

- “Jordanelle State Park Master Plan Final Report and Technical Data,” November 30, 1989

- Marilyn Curtis White, “Keetley, Utah: The Birth and Death of a Small Town“

- Michael O’Malley, “Too Close to Home: Keetley’s Japanese Relocation Farm“

More Utah Ski History

Park City nonprofit works to preserve site of America’s only underground ski lift