Snow

Utah’s deadly backcountry winter: experts say there is a false sense of security in managing risk

The aftermath of a near-deadly avalanche on Cardiac Ridge in Little Cottonwood Canyon on Feb. 11, 2025. Photo: Powderbird

How avoiding risk versus managing risk could prove to be the difference in reversing a concerning trend in U.S. avalanche fatalities

PARK CITY, Utah – With four fatalities recorded as of Feb. 14 for the winter season, Utah is experiencing a complex and deadly cycle as far as the snowpack is concerned. In addition to four people who have lost their lives, at least a handful of others have experienced serious, if not near-death experiences in the mountains.

Just last week, for example at Dutch Draw, located along the Park City ridge line, a group of skiers triggered a large-scale avalanche that broke from above and swept 600 vertical feel down the mountain fully burying one. Fortunately, due mostly to sheer luck, the skier was buried upright in seven feet of avalanche debris with her hand above her sticking out of the snow.

The official report said after locating the skier’s hand, rescuers cleared snow around her head before continuing to dig. She was successfully extricated without reported injuries.

Photos of the avalanche show multiple tracks in the easily-accessed terrain outside the Park City Mountain Resort boundary. The report said the skiers were equipped with backcountry rescue gear and that they ducked the resort’s boundary line, marked with a rope, and entered the closed terrain area.

In addition to the close call in Dutch Draw, avalanche forecaster Drew Hardesty said in a report posted on the UAC website on Feb. 11 that he had heard of two other “close calls” involving experienced and long-time backcountry skiers who unintentionally triggered separate avalanches along Cardiac Ridge, located north of Snowbird in Little Cottonwood Canyon and in the north bowl of Lake Peak in mid-White Pine of Little Cottonwood Canyon.

The Cardiac Ridge incident occurred on a high-elevation northeast slope where five people were skiing three days after a storm when a significant amount of graupel fell in Little Cottonwood Canyon. Graupel snow is a type of soft, small pellet-like snow often accompanied by strong winds and can create unstable snowpack, increasing avalanche risk.

One person was ascending on the skin track, one was on the slope and three were below.

“It looks like the skier was in an area with deeper graupel pooling from the main shot above,” the report said.

On the third turn, cracks shattered across the slope and the skier was able to see snow moving to his right as he skied left away from the slide. Another close call.

Failed attempts at risk management in the backcountry are on the rise

In Utah’s recent deadly avalanche season, experts caution that even with managed risk strategies, a false sense of security can prevail among backcountry enthusiasts.

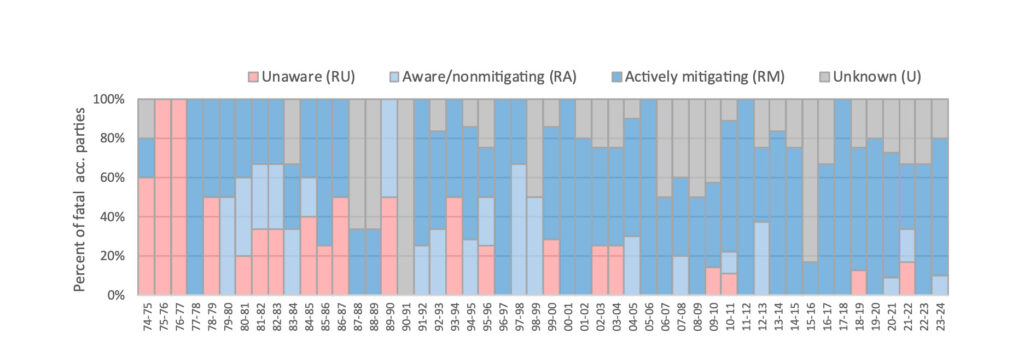

A report published in 2024 titled “Risk Management Trends In U.S. Backcountry Avalanche Accidents” shows that despite an increasing proportion of fatal accidents occurring to parties that said they had some level of formal avalanche education and had taken deliberate steps to mitigate their exposure or exhibited some level of competence at companion rescue – many accidents appear to be the result of failed attempts at risk management.

Utah’s most recent fatality, which occurred on Feb. 8, took the life of Higinio Juan Gonzales, 59, of Salt Lake City. Gonzales’s ski partner was seriously injured in the avalanche in Silver Fork’s East Bowl. Both men were reported to be experienced backcountry skiers.

The study, written by Ian McKammon and Kelly MNeil, shows that the majority of parties who were actively mitigating risk, did not use their skills to avoid the most dangerous slopes identified in the avalanche forecast. Similar to findings in two previous studies, this evidence suggests that knowledgeable parties used their avalanche skills to access avalanche-prone slopes during periods of instability. Worth noting, the study said, is that this trend appears to be increasing.

The 2024 study examined 240 accidents involving 424 people who were caught in an avalanche and 285 people who were killed. The study showed that of the accidents studied, 11% percent of people were categorized as unaware, 13% were aware of the hazards and a 56% were actively mitigating risk. The remaining 21% were categorized as unknown.

“It’s interesting how we manage risk, and that becomes the mindset, rather than avoiding risk,” Utah Avalanche Center forecaster and safety advocate, Craig Gordon said.

An expert’s advice: Avoid risk instead of trying to manage it

Gordon added that there are certain “avalanche dragons” or hazards that are manageable such as new snow avalanche problems, wind drifted avalanche problems, and storm snow avalanche problems, which can be managed with good decisions about slope angle and terrain choices as well as pairing those decisions with the avalanche forecast on a specific day.

“The other dragon that we’re dealing with is managed through avoidance. Avoidance is avoiding where that avalanche dragon lives. So, if that’s on the north half of the compass, I can take out that component from my run list for the day,” Gordon said

He added that the big avalanche dragon this year is what’s known as a Persistent Weak Layer (PWL). A PWL in avalanche safety refers to a buried layer of weak, unstable snow that remains prone to avalanching for weeks or even months after it forms. Unlike storm snow instabilities that bond quickly, PWLs can linger deep within the snowpack, making them especially dangerous.

“The persistent, weak layer isn’t managed. It’s avoided,” Gordon said.

Utah snowpack is often plagued by PWL problems, but Gordon said this year is especially tricky. With low snowfall in December, followed by a-typical storms bringing more maritime (dense and wet) quality snow to the Wasatch, plus several cycles of avalanches on the same slopes, known as repeaters, Gordon says it’s hard to take a birds’ eye view and recognize that although it is February, we are not dealing with a typical February snowpack in Utah this year.

“I think this is why it’s becoming tricky for even experienced people. It feels to me like right now we are used to seeing certain types of snowpack characteristics going into the middle of February and maybe we’re not recognizing that this is not a February snow pack. It’s more like a January snow pack, and that’s how we need to move around the mountains,” Gordon said.

Gordon cautioned that, in particular, slopes that face the north half of the compass are “guilty until proven otherwise.” He recommends people stay away from them, especially as another big storm sets its sights on Utah.

“There’s plenty of low angle love out there. I’m integrating a lot of terrain where the PWL doesn’t exist. And that right now, our slopes that face the south, they’re skiing brilliantly,” Gordon said.

The Utah Avalanche Center has issued an avalanche warning through the weekend. It reads: People should avoid travel in all avalanche terrain.

The warning has been issued for all the mountains of Utah and Southeast Idaho, including the Wasatch Range, Bear River Range, Uinta Mountains, Wasatch Plateau, Manti Skyline, the La Sal Mountains and the Tushar Range.

“Heavy snowfall and strong winds will create dangerous avalanche conditions, especially on northerly-facing slopes at the mid and upper elevations where avalanches may break several feet deep and hundreds of feet wide,” the report says.