Arts & Entertainment

Fatherhood, legacy, and grief collide in emotional Sundance doc “Third Act”

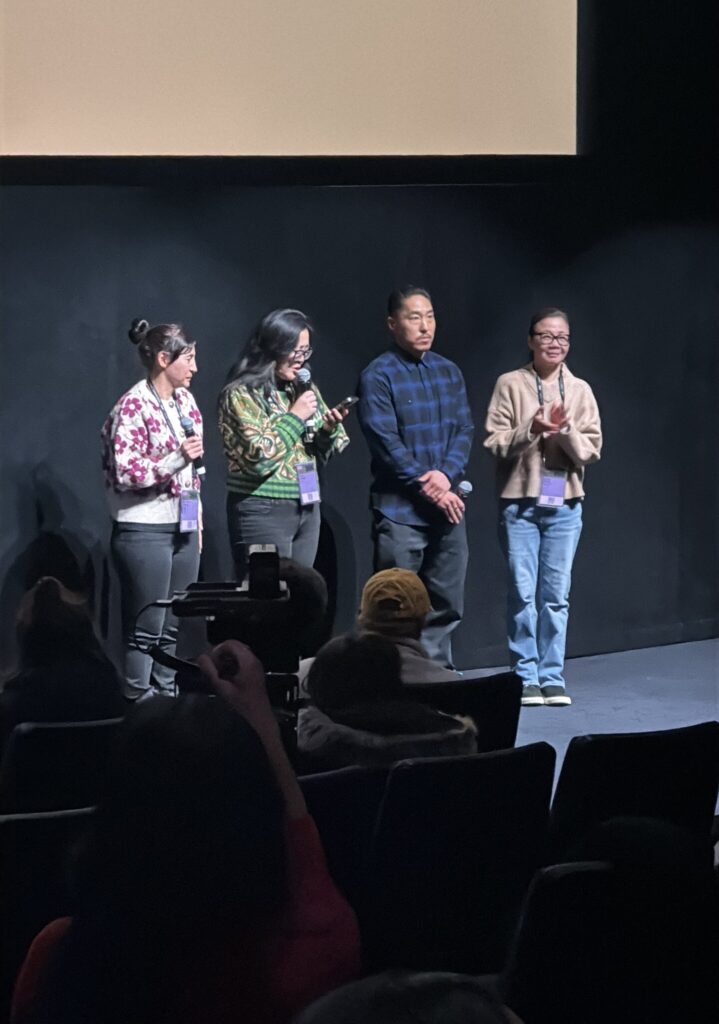

Miles Senzaki, Victoria Chalk, Eurie Chung, Tad Nakamura, Lou Nakasako, Alex Margolin and Jess X. Snow Photo: © 2025 Sundance Institute | photo by Donyale West/Shutterstock for Sundance Film Festival.

PARK CITY, Utah — Robert “Bob” A. Nakamura, often called “the godfather of Asian American media,” inspired generations of artists through his work as director and 33-year tenured professor at UCLA. However, for filmmaker Tadashi “Tad” Nakamura, that legacy is uniquely personal. His latest documentary, “Third Act,” explores his father’s life, career, and relationship as B. Nakamura confronts the challenges of Parkinson’s disease.

The film premiered to a packed audience on Jan. 26 at The Ray Theater, offering an intimate portrayal of art, activism, and family bonds. T. Nakamura grew up steeped in filmmaking and described how the project allowed him to connect with his father in a meaningful way.

“There was a point where I didn’t know if I was going to be able to finish this film and have him be here,” he said. “The fact that we’re all here together is a dream come true; that’s something I cherish.”

Nakamura’s personal history with filmmaking began early, even appearing as a baby in Bob’s acclaimed 1980 film “Hito Hata: Raise the Banner.” The film is groundbreaking as the first feature film about and by Asian American filmmakers.

The documentary features heartfelt interviews between Nakamura and his father, recorded as Robert’s health fluctuated. “Sometimes he wasn’t feeling well, and other times he had a good week, so we’d do two sessions in a row,” Nakamura said. “Those moments are something I’m very lucky to have.”

Robert explained on screen that he revealed and shared more in this film, because he was opening up to his son. With another filmmaker, he may not have been so transparent.

Throughout the film, it was easy to see that the process itself was an exercise in grief. As anyone who has experienced enduring an illness of a loved one, the grieving process begins before the actual passing of the afflicted. T. Nakamura explained in the Q and A that sometimes focusing on the film was an easy out, a distraction from what was happening before his family’s eyes.

Editing the film proved complex, with decades of archival material from Robert’s career alongside personal footage of the Nakamura family. Victoria Chalk, the film’s editor, described the challenge of weaving together the professional and personal aspects of the story. “It was about finding the balance,” Chalk said. “Ultimately, we focused on the father-son relationship, showing that Bob’s story is also Tad’s story.”

Producer Eurie Chung said as the filming was continuing and the story developed, it was almost as if the Parkinson’s diagnosis was the binder that catapulted the footage into the story arc it became.

The film was an exploration of four generations of the Nakamura family, including Robert, Tad, Robert’s father Harukichi Nakamura, and Tad’s son Prince. But beyond that, it was a study of self love and self hate, identity, racism, trauma, and healing. The film’s heart was Robert’s experience as a young boy at the Japanese war relocation camp Manzanar, where more than 100,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

B. Nakamura throughout the film found it easier to visit Manzanar and address the trauma that was buried for decades. He shared positives of the experience with grandson Prince, including finding sticks for slingshots and keeping scorpions and lizards as pets.

During a post-screening Q&A, audience members shared how deeply the film resonated. An attendee whose mother-in-law has Parkinson’s, praised the documentary and asked about plans for distribution. Nakamura emphasized the importance of reaching a wide audience, including a festival run and a planned broadcast on PBS’s Independent Lens in 2026.

The film concludes with a poignant moment between Nakamura and his own son, underscoring the continuity of family and legacy. Nakamura reflected on how the project helped him move forward. “I’m trying to share as much time as I can with my dad, but I also know there’s a future to build with my family,” he said.

“Third Act” is a moving exploration of family, identity, and the Asian American experience. With its deeply personal narrative, the documentary offers a profound meditation on what it means to honor one’s past while looking toward the future. It is certainly a film that allows for reflection no matter your race and will stick with the viewer long past the credits.