Politics

Utah governor vetoes 7 bills, tells lawmakers to stop legislating what could be ‘a phone call’

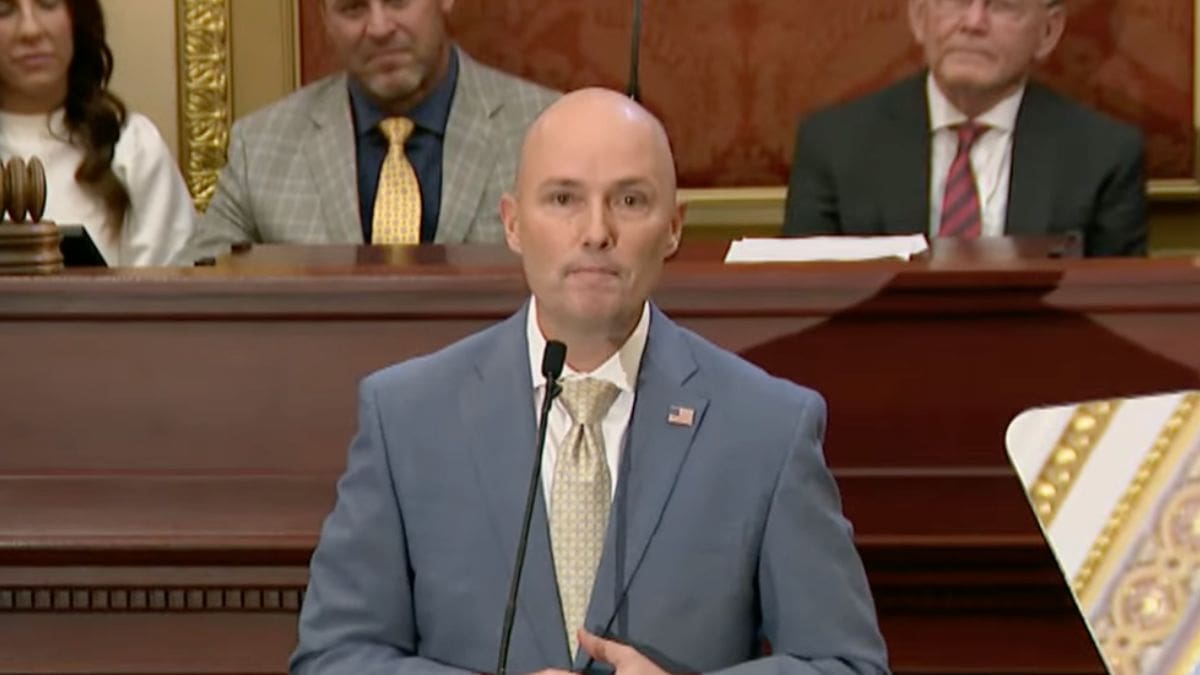

Gov. Spencer Cox delivers his 2024 State of the State Address, Jan. 18, 2024. Photo: PBS Utah

By: Katie McKellar, Utah News Dispatch

Utah Gov. Spencer Cox had a simple message for lawmakers when he announced which bills he’d vetoed:

Less is more.

Cox vetoed seven bills Thursday, the last day before his midnight deadline to deal with the record 591 bills the 2024 Utah Legislature sent to his desk.

The governor told reporters during his March PBS news conference on Thursday morning that he would be vetoing legislation that he essentially considered unnecessary and could have been “phone calls” to his office or state agencies rather than needing to be written into law.

“Just like there are meetings that could be emails, sometimes there are bills that could be phone calls,” Cox wrote in his veto letter to lawmakers. “We try hard to be responsive to legislative requests and I have instructed my cabinet members to do everything they can to help with issues and ideas you might have.”

He also said some bills may have started out with a more “substantive objective,” but they were later watered down “to a point that it does not effectively accomplish its goal.”

“Sometimes, instead of trying to pass something, the best result is to regroup and consider another run at the issue down the road,” Cox wrote.

While “we probably could have found more bills” to veto, Cox wrote, he chose seven. They were largely innocuous and noncontroversial, but Cox deemed them unnecessary. They included:

- HB152, which would have required the Division of Professional Licensing to create a sample contract for residential construction and remodels. “The Division can (and will) do this without a bill directing it,” Cox wrote.

- HB239, which would have required the Division of Technology Services to create a cybersecurity training program for executive branch employees, and requires them to complete it every year. “However, this training program already exists, and employees are already required to participate,” Cox wrote. “If there are concerns with the existing program, DTS stands ready to make whatever changes are needed.”

- HB412, which would have added additional items for an agency to report on as part of the accountable budget process — including an agency’s compliance with the Office of the Legislative Auditor General’s toolkit. “I am very supportive of the toolkit, and expect agencies to use the toolkit as a tool to improve organizational excellence,” Cox wrote. “But we don’t need a bill in order for agencies to apply the toolkit to improve operations.”

- SB244, which would have codified requirements for the Division of Professional Licensing to annually verify that criminal history guidelines published by the division accurately reflect the most current provisions of the Utah Criminal Code. Cox noted the division has already created criminal history guidelines and publishes the guidelines on its website — something it already does without the bill. “We can address the sponsor’s concerns without a bill, and I have directed DOPL to ensure that this happens,” Cox wrote.

- SB274, which would have required a report for a state agency that uses an administrative law judge. While the bill’s original version would move all of the state’s administrative law judges into the Utah Attorney General’s Office, it was changed to instead require them to report information to the Legislature. “Our agencies can provide this information without a bill,” Cox wrote. “I have tasked the Department of Government Operations with gathering the information sought.”

- HB144, which would have clarified that a driver intending to turn left is not required to yield the right-of-way to a vehicle operator approaching from the opposite direction that fails to stop when required by a stop sign or steady red signal. “In response to concerns, some of the language (of the bill) was removed,” Cox wrote. “The language that remains has raised concerns and may not bring the clarity that the original goal intended.”

- SB190, which would have required the Political Subdivisions Interim Committee to study issues relating to a university’s development of university-owned property. “While we agree with the initial policy direction of the bill, sometimes a bill changes direction in a substitute and doesn’t need formal legislation to accomplish our policy objectives,” Cox wrote. “We’ll still work with higher education and (the bill’s sponsor) Sen. (Chris) Wilson to explore this idea.”

Quality over quantity

Earlier Thursday, Cox foreshadowed his vetoes while also telling reporters he was overall “very pleased” with this year’s legislative session — especially when it came to funding and legislation dealing with his top priorities housing and homelessness.

However, he said he worried about the quantity and quality of legislation.

“My greatest concern with this legislative session was just the sheer number (of bills),” Cox told reporters. “591 is a big number.”

In his veto letter, Cox thanked Senate President Stuart Adams, R-Layton, and House Speaker Mike Schultz, R-Hooper, for the Utah Legislature’s work this year, but he had “just a little bit of constructive feedback” on the number of bills passed.

He included a chart depicting how the number of bills passed year to year has grown over the past two decades. In 2005, Utah lawmakers passed 370 bills. In 2024? Just shy of 600, with 591.

“While I suppose there is nothing inherently wrong with more bills,” Cox wrote, “I truly believe it makes it more difficult to focus on the quality of legislation.”

Cox added he’s not asking Utah lawmakers to be “like our dysfunctional Congress, which somehow only passed 27(!) bills last year. While I would love to get back to the 300s, maybe shooting for the high 400s is a more realistic goal.”

Why doesn’t the governor veto more?

Asked why he doesn’t veto more bills, Cox said, it’s “really easy” to “just flippantly veto bills, (but) the minute I do that, nothing I would like to get passed gets passed. … The more you veto, the more likely you are to get overridden.”

The governor acknowledged the process can get political — and personal.

“I’ll override yours if you override mine,” Cox said. “That’s how it works.”

He said it’s “very possible” that lawmakers could call a veto override session to overturn any of his vetoes, “which is how this works. And that’s OK too.”

“I’ve been there. I’ve been a legislator. I get it. It’s not fun when you have a bill vetoed. And that’s why we try really hard not to do it, “Cox said.

Cox noted he sometimes signs bills even if he doesn’t like them — but he declined to name any of those bills, saying “that kind of defeats the purpose” as he negotiates with legislators to make sure his priorities make it across the legislative finish line.

“We had bills that were really important to us that we had to work hard to get done,” he said, pointing to late-session negotiations around more than $50 million in homelessness funding, for example. He said the Legislature didn’t have to support those priorities, but they did.

“They passed a bill that they didn’t like to help me get one of my priorities through, which means that sometimes I have to sign some things that I don’t love because that’s the way this works,” Cox said. Though he added, “I would never sign something that I thought did lasting harm to Utah. But if I could get it to a place where I could live with it even though I don’t like it, then I’ll go ahead and sign it.”